Unconfined by Expectation

Los Angeles Central Library review on LA Review of Books

by Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

LOS ANGELES BOOMED in the early decades of the 20th century, and its political, business, and civic leaders scrambled to keep up with the infrastructural needs of this burgeoning population. An aqueduct was built to bring water, a port to handle cargo, an inter-urban streetcar system to move people, and new thoroughfares extended from the downtown center in every direction. But one vital element of the infrastructure, a world-class public library, was long in coming. A small reading room with a few books and newspapers in an adobe on North Main Street offered a start in 1844, and growing pains soon led to other temporary locations. The Los Angeles Library Association was formed in 1872, but many years passed before a permanent location was found. Finally, after more than 80 years of moving from place to place, the new Central Library was dedicated in 1926.

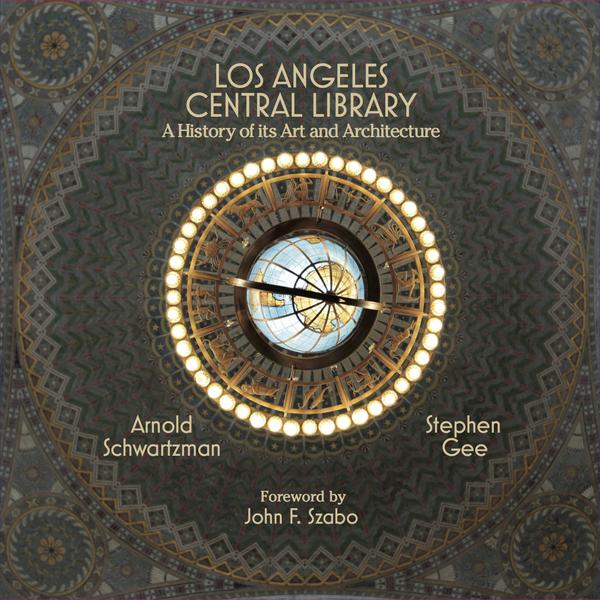

The story of the Central Library as told by Stephen Gee (with wonderful photographs by Arnold Schwartzman) focuses on the building’s architectural design and artistic motifs — its sculptures, murals, and interior paintings. The story begins with architect Bertram Goodhue. As conceived by Goodhue, the plans for the Central Library repudiated the then conventional Greco-Roman library architecture in favor of bold cubist and modernist forms. These served as a framework for motifs that reflected Goodhue’s explorations of Europe, Mexico, Egypt, and Persia. To top it off, Goodhue crowned the plan with a tower modeled in part on his submission for the 1922 commission to design the headquarters for the Chicago Tribune. The result, as Gee describes it, is “an exotic blend of Spanish, Egyptian, Byzantine, and Islamic influences, the vision of an architect at his peak unconfined by expectation.” In order to underscore visually just how “unconfined” Goodhue’s vision really was, Gee reproduces an alternative drawing prepared by Siegfried Goetz in 1917 as well as a Beaux-Arts design by architects Dodd and Richards, both of which seem remarkably tired and formulaic by comparison.

The story of the Central Library as told by Stephen Gee (with wonderful photographs by Arnold Schwartzman) focuses on the building’s architectural design and artistic motifs — its sculptures, murals, and interior paintings. The story begins with architect Bertram Goodhue. As conceived by Goodhue, the plans for the Central Library repudiated the then conventional Greco-Roman library architecture in favor of bold cubist and modernist forms. These served as a framework for motifs that reflected Goodhue’s explorations of Europe, Mexico, Egypt, and Persia. To top it off, Goodhue crowned the plan with a tower modeled in part on his submission for the 1922 commission to design the headquarters for the Chicago Tribune. The result, as Gee describes it, is “an exotic blend of Spanish, Egyptian, Byzantine, and Islamic influences, the vision of an architect at his peak unconfined by expectation.” In order to underscore visually just how “unconfined” Goodhue’s vision really was, Gee reproduces an alternative drawing prepared by Siegfried Goetz in 1917 as well as a Beaux-Arts design by architects Dodd and Richards, both of which seem remarkably tired and formulaic by comparison.

The heart of the book is Gee’s detailed and riveting description of the architectural work of Goodhue, as well as the significant contributions made by others, including Carleton Winslow, the associate architect thrust by Goodhue’s sudden death in 1924 into the crucial position of selecting the construction firm that would erect the structure and the artists who would decorate it. Winslow guided the day-to-day operations, negotiated contracts, and interfaced with the Library Board, the mayor and City Council, and the Municipal Art Commission. Lee Lawrie, one of the United States’s greatest architectural sculptors, created the library’s iconic exterior and interior fixtures, including the historic figures above the Hope Street entrance and the fountain in the children’s court. Julian Garnsey painted the rotunda, ceilings, and walls. Dean Cornwell designed and painted the murals featuring California history in the rotunda. Muralist Albert Herter decorated the first floor lobby and the Hope Street tunnel. Gee devotes a chapter to each contributor, providing fascinating biographical information and describing their many artistic and personal challenges and accomplishments. Preliminary drawings and sketches, early models of sculptures, and blueprints are juxtaposed with Arnold Schwartzman’s photos of the finished products. The inclusion of dozens of arresting, richly colored images in this oversized book are a credit to the publisher, Angel City Press, which bravely specializes in books that demand and deserve a rich tapestry of illustrations.

Gee’s narrative also allows us to appreciate how skillfully and inventively librarian Everett Perry navigated this complicated project through a shifting minefield of political obstacles, which imperiled it at every step of the way. From agreeing on a location to assembling and purchasing the parcels of land, determining the bidding process, and, finally, selecting an architect, Perry worked assiduously to overcome a cacophony of objections from members of the Library Board, the mayor, the city councilmembers, the Municipal Art Commission, editorialists and writers from The Los Angeles Times, and any number of self-appointed critics with various axes to grind. Eventually, the Weymouth Crowell construction firm (which had built the Los Angeles Athletic Club and the Ambassador Hotel) was selected and broke ground on the Flower Street property in November 1924. In July 1926, more than 500 invited guests gathered in the rotunda for the formal dedication of the Central Library. Eighty years after the first little reading room opened, with little fanfare, on North Main Street, the people of Los Angeles finally had a library of their own.

The story might have ended there, on a high note, but Gee takes the harder route and chronicles an even greater challenge to the library’s existence half a century later. A chapter entitled “An Uncertain Future: What To Do With The Library?” describes how concerns about increased demands from a much larger population, parking issues, shortages of space for books, lack of air conditioning, costs of repairs, nonworking elevators and telephones, and other shortcomings produced a rising tide of demands for the library to be demolished and rebuilt somewhere else. The Library Board concurred with this opinion and convinced the City Council to place a bond for the construction of a new building on the citywide ballot in May 1967, but voters rejected the initiative. For 20 years, opinions about the future of the Central Library were batted around by civic and political leaders without resolution.

Ironically, it was the threat of destruction by a fire in 1986 (later determined to be arson) that ultimately saved the building. Fear that the library would be destroyed immediately galvanized public opinion and 1,700 volunteers rushed to save volumes damaged by the fire in what proved to be one of the largest book-salvaging efforts in the nation’s history. More importantly, the rapid and unequivocal response of the people pushed hesitant business and political leaders off dead center and into action. The initiation of a “Save the Books” campaign brought in corporate donations of $10 million to restore and expand the library, setting the stage for another of Gee’s chapters, the 1993 addition of the 330,000 square foot Tom Bradley wing, designed by Norman Pfeiffer.

Today the Central Library is the third largest in the nation, and, according to Business Insider, is the second most beautiful (behind the NYPL). As Gee notes, “the Central Library remains a place where citizens, regardless of their economic status, can educate themselves and share in the power of the written word.” The library provides free access to information that enriches, educates, and empowers the city’s residents — and it has moved with the times: today’s patrons use computers and wireless internet to read books, download music and videos, and tap into an array of subject databases. Digitization projects have helped to protect rare and fragile items in the library’s collections while making them more accessible to the public online. The library also reaches out to the community through a wide array of programs and services. Special cultural projects allow librarians in the neighborhood branches to host events and activities that motivate community members to engage with classic literature and with writers in their communities.

It’s relatively easy to place an economic value on a piece of physical infrastructure. Today we are rebuilding the Sixth Street Bridge that spans the Los Angeles River. Before construction began, we were assured what the cost would be in dollars and what the benefit would be in terms of safety and more rapid movement of traffic. The same holds true for other infrastructural projects, such as connecting Downtown with Santa Monica by light rail or widening the 405. But it is always more challenging to impose the same sort of cost-benefit analysis on the intellectual infrastructure of our cities: our libraries, schools, colleges and universities, newspapers, museums, bookstores, research institutes, and literary journals. The story of the Central Library reminds us of the value of our intellectual infrastructure — and of vital need to defend it, from above and below.

¤

Darryl Holter is a historian, entrepreneur, musician, and owner of an independent bookstore. He has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC.

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.