Back In The Saddle Again

Oliver Holter, my father, died this week at the age of 100. I was with him on September 1 for his 100th birthday. He died peacefully in his sleep under the loving care of my sister, Cyndy and niece, Kiera. Here is Dad’s obituary and a section from a book I wrote for him to commemorate his 80th birthday. Dad introduced me to music as a child and taught me how to play guitar.

-DH

From OLLIE80: Memories of My Father and I (2002)

By Darryl Holter

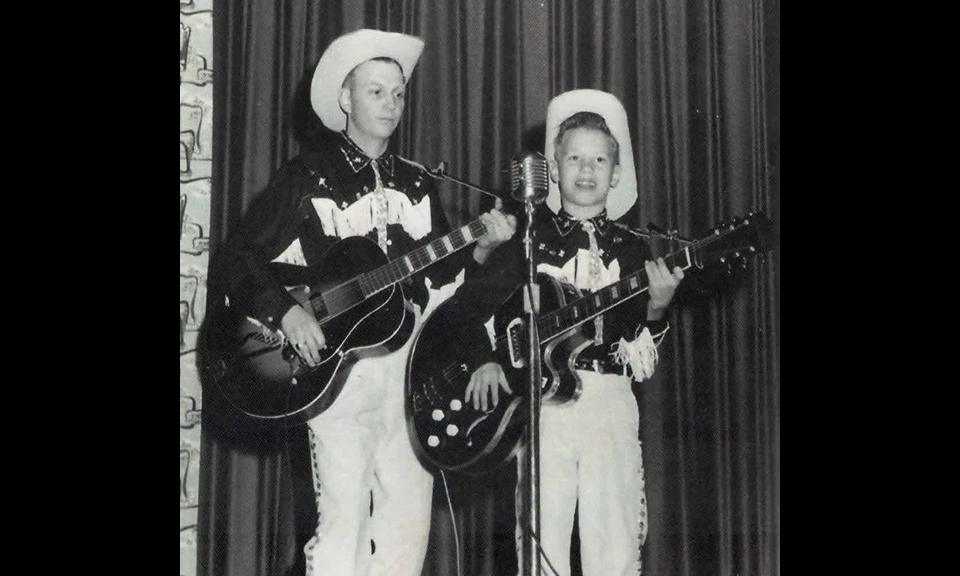

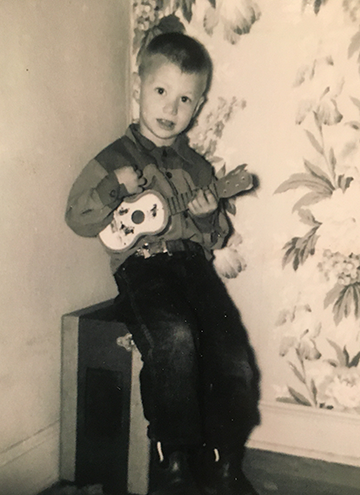

Like a lot of young boys, I was attracted to cowboys. My mother used to make me cowboy shirts that I wore all the time. I always had some kind of cowboy hat. I would put it on and look in the mirror to see if I looked very authentic. I never had much experience with horses, but I was always ready to beg for a dime from my Dad when we went to Sears’ or to a hardware store when there was a mechanical pony that I could ride. It was partly because of this interest in cowboys that I came to share my father’s interest in music. From the time I was very young my parents had taught me how to sing songs. In those days none of our cars had radios and we often sang together in the car. Then my parents often took me to church and Sunday school where we used to sing simple church songs. My father loved country western music. He had taught himself how to play the guitar by studying books and had purchased a brand new Gretsch Synchromatic arch-top guitar after returning from the war. It had an electric pick-up and he added an amplifier and was very proud of this beautiful new instrument. One of my Dad’s friends was named Harry Miller, an accomplished musician who played guitar, saxophone, and clarinet. Sometimes my father played informally with Harry, who performed with the somewhat famous group called the Harmonicats. My mother liked Harry’s wife, I think, and they used to socialize when I was quite young.

Sometimes after work or on the weekends my father would bring out the guitar and I used to sing along to his songs. We sang songs like “Back in the Saddle,” “Cool, Cool Water,” and “San Antonio Rose.” We sang them so many times that to this day I recall most of the words. My father also had a laptop Hawaiian steel guitar that I considered quite exotic. Dad had served in the Pacific during the war and had spent some time in Honolulu. Among the G.I.s the Hawaiian sound was quite popular. I watched with amazement as he attached special plastic or metal picks to his right hand fingertips and thumb while using a steel bar in his left hand to create a unique and pleasing metallic sound. Somewhere along the way I had received a plastic toy guitar with four strings, but I was not allowed to play with my father’s serious guitars. But one day he brought home a real guitar for me to use. Dad found a rope that we used as a strap so I could hold it up. Now I was in business!

Dad set me down in front of a music stand and took out some simple music and began to show me how the strings represented notes and how these notes would change as I moved my finger along the frets on the neck of the guitar. He explained how to tune the guitar and showed me the scales using catchy ways to remember their order (“E-G-B-D-F“could be remembered by “Every Good Boy Does Fine”). With good reason my father wanted me to learn the basics of note reading prior to learning chords. He could place the sheet music on the music stand and play notes with some facility. When he came to a part that he hadn’t mastered, he continued to stop and start until he had it down, and then moved on. When I followed his example, however, I soon became bored. He would encourage me to keep trying, but I began to rebel against this aspect of learning the guitar. This was quite stupid on my part, since knowing how to play notes and read music is basic to being a musician. Yet I resisted his efforts to teach me to read music and I used to make excuses to leave, such has having to go to the bathroom, and I would leave my Dad playing by himself. Sometimes we had arguments over this behavior and finally my Dad told me that if I didn’t want to learn there wasn’t much he could teach me. He did, however, begin to teach me some simple two-finger chords, C, F, and G and I found that I could play along with him when he played in the key of C.

Dad set me down in front of a music stand and took out some simple music and began to show me how the strings represented notes and how these notes would change as I moved my finger along the frets on the neck of the guitar. He explained how to tune the guitar and showed me the scales using catchy ways to remember their order (“E-G-B-D-F“could be remembered by “Every Good Boy Does Fine”). With good reason my father wanted me to learn the basics of note reading prior to learning chords. He could place the sheet music on the music stand and play notes with some facility. When he came to a part that he hadn’t mastered, he continued to stop and start until he had it down, and then moved on. When I followed his example, however, I soon became bored. He would encourage me to keep trying, but I began to rebel against this aspect of learning the guitar. This was quite stupid on my part, since knowing how to play notes and read music is basic to being a musician. Yet I resisted his efforts to teach me to read music and I used to make excuses to leave, such has having to go to the bathroom, and I would leave my Dad playing by himself. Sometimes we had arguments over this behavior and finally my Dad told me that if I didn’t want to learn there wasn’t much he could teach me. He did, however, begin to teach me some simple two-finger chords, C, F, and G and I found that I could play along with him when he played in the key of C.

When I was five years old my parents signed me up to perform on the Jimmy Valentine television show, a Saturday morning talent show for young children on KSTP. I didn’t play the guitar well enough so I sang “Back in the Saddle” and Dad accompanied me outside of the range of the camera. Prior to the beginning of the show, I saw all the toys that were to be offered to the performers. I was infatuated with a “Slinky” that I had seen on television. My parents told me to select the big tricycle instead. No, I wanted the slinky. “O.K.”, they said, “if you can win the bike, take it, and we’ll go out and get you a Slinky.” I sang “Back in the Saddle” and won the right to select the gift of my choice. I chose the bike and later got the Slinky as a bonus. After a few days the Slinky got kinked up and didn’t work so well, but the tricycle served me well until I graduated to a two-wheeler.

Dad encouraged me to continue playing the guitar and I got better on the simple chords progressing from using two fingers to three, but I still resisted learning to play notes and to read music. I remember my father helping me to place my fingers properly on the strings. The positions seemed awkward and it was somewhat painful to hold my fingertips tightly against strings where they crossed the frets on the neck of the guitar. In our household we continued to sing songs and at family gatherings my parents would encourage me to sing a few songs. I found it easy to memorize the words and soon lost any fear of singing in front of people. During this period I remember a couple of early summer mornings when I walked two blocks to a little bakery located on 24th and Bloomington. I would go to the back door off the alley and knock politely at the door. The ladies working inside came to the door and I told them I would sing them a song because I really liked cinnamon rolls. They laughed and I sang one or two songs. They gave me a couple of rolls and I ate one and brought the other one home.

We had a little record player, and I took it into the basement and started to listen to Dad’s country records. I listened to them and started to play chords along with the records which worked for me when they were played in the key of C or G. Then I started to sing along with my strumming until I had learned the song and could play and sing it myself. One Saturday afternoon I was playing in the basement and Dad heard me and came down the steps. He hadn’t heard me play for several weeks and he sat and listened until I finished the song. He said, “Well, Darryl, you sound pretty good, and you play Ok even though you don’t know how to read or play notes. But keep going and you’ll get better.” This made me feel great and I was so glad that Dad had heard me play. Later that day I walked to the record store at 66th and Penn and bought a record by Elvis Presley, “Hound Dog” and “Don’t Be Cruel”. Dad opened the music door for me.

Oliver Sivert Holter

September 1, 1922 – November 8, 2022

Oliver Holter passed away at the age of 100 on November 8, 2022. “Ollie” was born on September 1, 1922 in Caledonia, Minnesota and was the youngest of five children born to Sivert and Dora (Moen) Holter. Ollie never knew his father, who died of tuberculosis while he was an infant. With five children and no husband, Dora tried to keep the farm going, but an accident with a horse-drawn hay wagon resulted in a leg amputation. At that point, she moved her family to the near-northside of Minneapolis.

In grade school Ollie contracted rheumatic fever and was hospitalized for nearly a year. After recovery, he resumed his studies and also developed, on his own, incredible mechanical skills. Without a father, yet as an avid reader of Mechanics Illustrated and Popular Mechanics, Ollie learned how to fix anything. At age 14 he purchased and rebuilt an old beat-up Ford Model T. Ollie entered Vocational High School and studied printing, gaining expertise in operating, maintaining and repairing all types of printing presses. His senior year was interrupted by the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and he graduated early to enter the Army Air Force. Stationed in the Pacific, Ollie rose in the military ranks to become a Staff Sergeant. He returned to Minneapolis and surprised his family on Christmas Day 1945.

A few months later, while picking up an automobile part at Sears on Lake and Chicago, Ollie ran into a former high school classmate, Helen Cook, who was also studying printing. He offered her a ride home, she offered him some lemonade, he suggested they go out to a roller-rink, she agreed and soon they were on their way to 75 years of happy marriage. They both worked in the printing industry until retirement. Their marriage brought them great happiness, and Helen bragged that Ollie kissed her goodnight every night. They were together until Helen died in March 2020.

Ollie’s mechanical skills were legendary in our family. Not only could he repair and rebuild printing presses and automobiles, but Ollie mastered plumbing, electrical, and carpentry. In three homes he turned unfinished attics into beautiful bedrooms for his growing family. He also loved music and taught himself how to read music and play the guitar.

In the last months, days, and hours of his life, Ollie was lovingly cared for by his daughter Cynthia and granddaughter Kiera. He was warmly loved by all the members of his family including his four children, Darryl (Carole Shammas), Cynthia Kantrud (Steven Kantrud, deceased), Darwin, and Jillayne, grandchildren Aaron, Rachael, Kiera, Sonia, Julia and Sasha, and great grandchildren Steven, Calder, Rosa, Evan, Simone, and Yvaine. Funeral services for Oliver (and Helen, whose service was postponed in 2020 due to Covid) will be held at Lakewood Cemetery on December 3, 2022.

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.