LARB Review: L.A. and the Birth of Car Culture

L.A. and the Birth of Car Culture: On Darryl Holter and Stephen Gee’s “Driving Force”

Los Angeles Review of Books By Gary Cross

WE ARE ACCUSTOMED to thinking of the car as an inevitable fit for America and Americans when it appeared around 1900. A spread-out people, already accustomed to personal travel by horse, with an often-noted aversion to crowds, made the conversion to mechanical automobility easy. Nowhere was this more evident than in the region of Southern California. In 1900, Los Angeles was a new city, free from the density and labyrinthine streets of the old walking towns of Europe or even New England; it had attracted settlers (and developers) expecting personal space but also the easy access to work and shopping the car alone could provide. The city had weather that accommodated early roofless and unheated vehicles that in New York might have needed to be stored during winter. Even the early L.A. trolly system paved the way for the car by fostering dispersal and the subsequent need to fill in the gaps between the web of trolly lines with cars and roads. But, as Darryl Holter and Stephen Gee’s recently released book Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City, 1900–1930 claims, Los Angeles as the United States’ quintessential car town cannot be reduced to such abstractions. People, even individualistic people, made it happen.

Most books about the people in this field have focused on heroic inventors and manufacturers like Henry Ford and Alfred P. Sloan, or the workers in automotive factories and their union led by Walter Reuther, or even promoters of highway and freeway construction like Robert Moses in New York. Interestingly, these figures came from—and gained fame from—their activities in the East. This seems odd, given the size and impact of cars on the West, especially Los Angeles. Even odder, this attention to manufacturing and infrastructure ignores a most vital fact: at the beginning of the car industry, Americans had to be won over to cars. In retrospect, this seems obvious, but it was not so in 1900. Not just cars but a vast array of new consumer goods that were mass-produced had to be sold to a sometimes reluctant populace. Advertising and new labeling may have impelled American men to buy Gillette razor blades and mothers to purchase Jell-O, but cars were different. They were complex, often unreliable, and, most of all, expensive machines (costing in 1900 about twice as much as the average yearly wage). Crucially, they demanded skilled operators on poor and often dangerous roads.

Winning a commitment to such devices required enthusiastic and persuasive salesmanship, but also repair services and even financing. And carmakers provided none of this. The driving force of car consumption was much more than just an American “natural” love of automobility (or even their promotion, via massive advertising). The vanguard of the new consumer culture was the car, and its leading edge was arguably the car dealer. And Driving Force argues that Los Angeles was home to some of the most important retail innovations.

The car dealer has long been written off as the mere go-between, or else maligned (especially in used car sales) as at least a slightly shady operator, certainly not in the mold of the heroic inventor Ford or the corporate genius Sloan. Yet it seems that these men (and, as noted in the book, also some women) shaped and made possible the revolution from hoof and rail to automobility in the early 20th century.

It is no surprise that this scholarly topic arrived as late as it has. And perhaps such a book could only be written by Darryl Holter, a scholar whom I have known for decades but also someone who has decades of experience in car retailing and dealership management on Los Angeles’s Auto Row on Figueroa Street. Holter took over his father-in-law’s business in middle age. Not only has he enjoyed a lifelong engagement with American folk and popular music, but he was also trained as a modern social historian and taught at UCLA. When, through his connection with the California New Car Dealers Association, he came upon an archive of dealers’ documents, he decided to write their history. The result is not an academic tome: it was edited for a wider audience by local architecture authority and television producer Stephen Gee, who found and arranged in the book an interesting and attractive array of local photos and car-themed cartoons and ads, illustrating L.A. car culture during its formative years.

The result is an unusual book. Most chapters reflect a dealer’s perspective—e.g., “Auto Rows and Retail Facilities,” “Selling Cars on Credit,” “Service and Repairs,” and “Used Automobiles.” But Holter’s treatment of these themes goes beyond business issues to show how the first generation of car buyers were sold on automobility. Although Driving Force avoids the polemics of academic history, it insists that the retailer was irreplaceable. In the early years, carmakers were hardly prepared to lead the automobilization of the United States. By 1910, there had already existed nearly 500 of these enterprises, nearly half of which soon failed. Most were essentially parts assemblers with little capital or capacity for distributing and selling their products on a national scale. Instead, retailers had to supply the capital to manufacture early cars by winning customers who ordered cars to be custom-built. Neither manufacturers nor banks would provide consumer credit for purchasing such an untested product. Dealers found that they had to offer down payments and credit to consumers. Parts were unstandardized down to nuts and bolts, causing a nightmare in repair for which manufacturers provided little help. This, too, required local ingenuity. Of course, manufacturing innovations (culminating in Ford’s assembly line of 1913), created mass production and a steady flow of vehicles to dealer showrooms and lots. Still, though Ford tried for a time to directly retail the Model T, most car companies adopted a franchise system of independent dealers that offloaded a lot of risk to retailers.

Central to Holter’s story is the transformation of the car from a toy of the rich to a democratic right and necessity—a shift that required more than the assembly line. The car became the central product of an American revolution in mass consumption because it became affordable to the many and because the many were won over to its necessity. Part of this was the work of retailers like those on Los Angeles’s Auto Row.

Making cars affordable to the average family required consumer credit just as home ownership did. At first, dealers sold all cars on a cash basis (in part because manufacturers demanded large deposits to build cars on order). But soon, dealers offered down payments, leading, in the 1910s, to finance companies providing car loans, thus making possible middle-class car ownership. As early as 1925, 75 percent of brand new cars purchased in Southern California were done so on installment plans, even if they were only for a short term of two years or less.

A second innovation also eased entry into car culture: the used-car trade-in. This made new cars affordable to many and the sale of those used cars accessible to still more. Dealers at first resisted opening used car divisions. Like used clothes, dealers in a luxury item such as early cars thought selling them used was degrading—like high-end dress shops selling used skirts. Yet, as fewer customers were first-time buyers and more needed financial incentives to buy new, trade-ins became the norm. This was not always advantageous to dealers who, when pressed into selling new cars, had to offer unprofitable trade-ins. Still, the logic of the used-car market greatly expanded ownership: by 1923, while 3.6 million new cars were sold in the United States, there were 2.8 million trade-ins. Given the variety and different vintages of used cars, finding a “fair” price was a problem for both buyer and seller, producing the need for a reliable price guide for used cars, which was eventually provided in 1926 by Leslie “Les” Kelley, of L.A.’s Kelley Kar Company, in the form of his business’s inaugural Blue Book.

Winning commitment to the car required more than making it affordable. Cautious customers needed assurance that the car could be fixed when it broke down, as it did far more often than today. Bad roads and driver misuse and ignorance were compounded by the lack of car manuals and standardized parts, creating demand for the hit-and-miss work of auto mechanics. Car dealers, of course, opened service departments but also pushed manufacturers to improve parts and service training. These seemingly prosaic advancements made US car culture possible .

Less tangible, but no less necessary, was how dealers created a mystique around the car and its possession. Though automobiles were known as practical machines of mobility, which were first sold in the often cramped and dirty settings of machine shops and livery stables, dealers soon realized that their cars could represent not simply vehicles of transport but, rather, expressions of status for an emerging middle class. Dealers learned to display and glamorize their autos, just as modern downtown department stores did their suits and gowns. Such expectations have largely disappeared from our discount shopping world. But early in the 20th century, with many of the new sites of consumption, dealers concentrated their showrooms downtown, usually near each other on a succession of auto rows (first on Main Street and then, by the 1910s, on Figueroa). Dealers in Packards, Lincolns, Stutzes, and Chandlers moved to architect-built structures, often multistoried, with well-lit showrooms and upper floors for parts, used cars, and repair—a surprisingly early application of the concept of “full service” at a time when most business was small and often specialized. These buildings suggested not only elegance but also efficiency—they were emblems of progress.

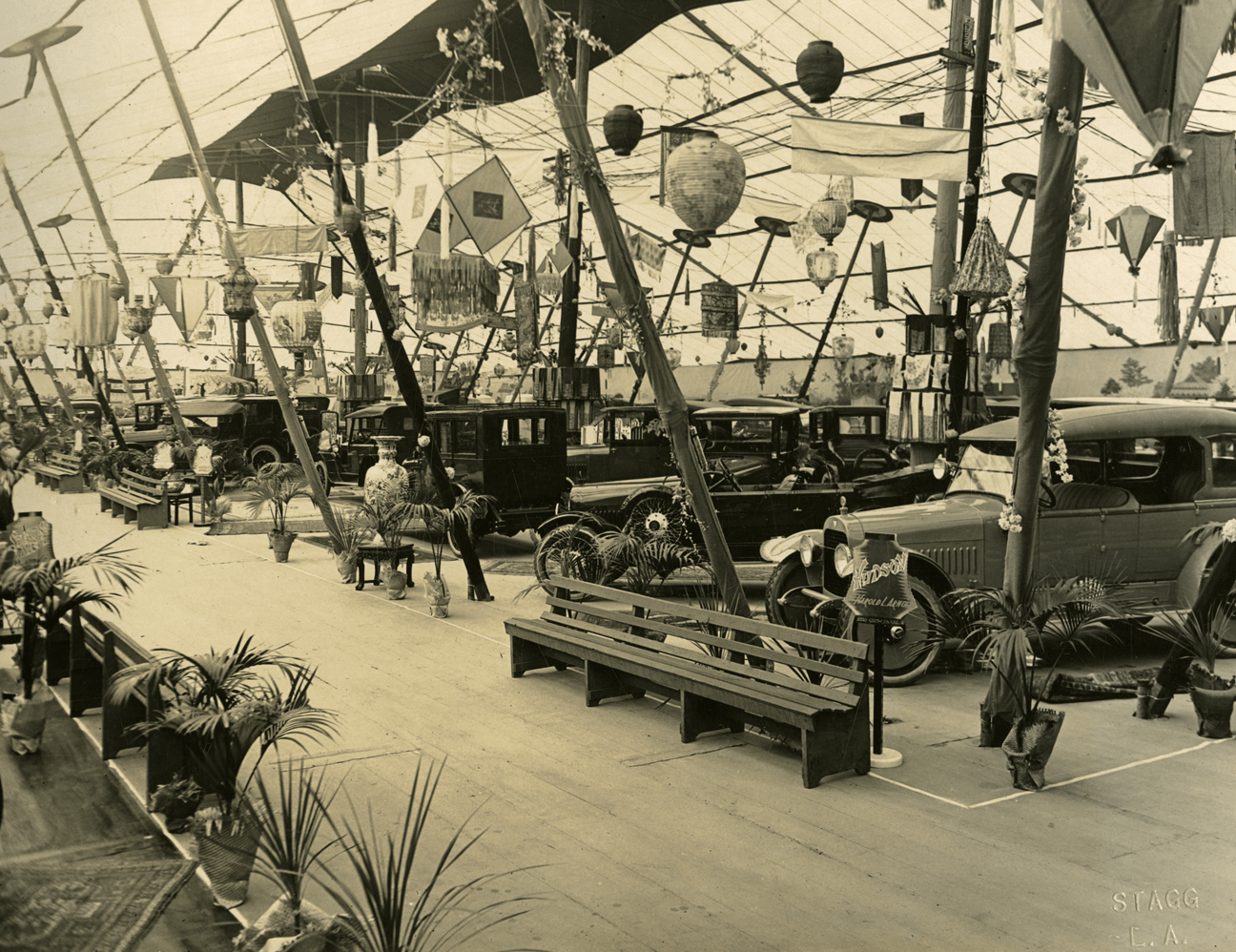

These car dealers were at the center of a modern age of commercial spectacle. They entered their cars in races. But they also sponsored frequent car shows with increasingly grandiose displays and luxurious settings. Auto shows became modern festivals of timely glamor and the sublimity of progress, often set, like the traditional festival, at special times and places. Car shows were very different from the everyday commercialism of the dealer showroom; they were even called the “social event of the season,” though their object was primarily to sell cars. Promoted by leading dealers and local officials from 1907, the shows became sites of boosterism and even cross-city competition. Rival dealers tried to outdo each other with decorations. One show was bedecked with expensive colored Chinese lanterns, and even enormous vases and ornamental plants, further adding to the aura and allure.

The history of human mobility has long been dominated by men: horses, wagons, trains, and ships. And so it was in 1900, as many saw the car as a modern horse (complete with horsepower). But this was also the age when women were beginning to break from Victorian and traditional constraints and conventions. Holter describes women running dealerships, but also women extending traditional female social and community service with their involvement in pressure groups for car safety and better roads. In the pioneering days of the automobile, women also entered endurance races, and a few tinkered with customizing cars. More conventionally, in a growing consumer culture where women were becoming the primary shoppers for many new products, women’s “interests” in comfort and convenience began to be considered in car design. Especially designed for women were electric cars, noted for their ease of start-up—without the front crank of early internal combustion vehicles, which was replaced in 1913 by the electric starter.

Holter takes seriously the personal element in explaining all this. Complementing these themes are a series of biographical sketches of major players in this story. The long-forgotten first car dealer, William K. Cowan, like many others, was a Midwestern migrant to Los Angeles, starting life in the jewelry business before entering the car trade, through operating the Rambler Bicycle Shop in the 1890s before its eponymous manufacturer switched to making cars. From these seemingly accidental beginnings, he promoted the industry with races and diversification in trucks. Ralph Hamlin—whose early skills led him to build, repair, and race, in succession, bicycles, motorcycles, and cars—secured a Franklin dealership. Angelenos will recognize the frequent references to the addresses and sites of Cowan’s shop and those of many other entrepreneurs, whose stories are told here. Many early dealers were closely associated with the emerging movie business (like Don Lee), or quickly entered or became connected with other avant-garde businesses: service stations (Earle Anthony), radio and TV (again Lee and Anthony, as well as Paul G. Hoffman), and even cartoons (Winslow Felix). Selling cars was about turning a profit, but it was also about being part of an ongoing enthusiasm for modernity in all its forms. Dealers not only arguably introduced Americans to the vehicle of modern life but were also often in the vanguard of a fast-paced and rapidly changing world of media and consumer culture.

In his afterword, Holter notes that Los Angeles has become “synonymous with gridlock, freeways, smog, high insurance rates and permit parking and yet the bond between people and their cars remained as unbreakable as it ever has been”—with the county counting 6,386,830 cars in 2021. For better or worse, the car culture that these early-20th-century dealers promoted remains securely in place 100 years later.

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.