Left Bank Blues: Adventures in Paris 1975

Left Bank Blues

Darryl Holter Adventures in Paris 1975

By Darryl Holter

When my daughter Julia was studying music at the University of Michigan she enrolled in a one-month course on “counterpoint” music at the Nadia Boulanger Institute in Paris. Not long after she arrived in Paris I had to have two wisdom teeth removed. Following the procedure I couldn’t really go to work for two days so I just sat down and wrote this little piece to send Julia recalling my own first experience in Paris.

Although I haven’t looked it over for many years, I do think that it captured a sense of what the City of Lights looked to a twenty-something in the mid 1970s. It was an exciting time, a different time, a different world in many ways.

– DH

1

I left Madison, Wisconsin in February 1975 for a three-month research trip to France. My dissertation concerned the coal miners and all the gory details surrounding the war, the nationalization of the industry, the strikes, and the cold war. The History department gave me an award of $500 for travel money and Harvey Goldberg, my advisor, had arranged for me to take over the little maid’s room on the sixth floor of his apartment building in Paris.

But first I had to get there. I found an outlet that specialized in cheap flights to Europe. You had to go to New York City and pay cash to fly out the next day. I had made arrangements with a friend who was planning on driving back, but those plans fell through, so I took a greyhound to Chicago and flew to New York. I carried a brown canvas bag and a beat-up but very useable red camping backpack, larger than the backpacks used by students today. I had a lot of books to carry and didn’t bring much in the way of clothes. In New York I stayed with a friend from Madison, Laura Kumin, who had started law school at Columbia. She lived on the upper west side on West End street. To get my plane tickets I hiked south to somewhere around 42nd street to small, no-name office in a no-name building. They sold me a one-way ticket for a flight leaving in two days for $176. On the way back to Laura’s a guy tried to rob me on a side-street, or at least he threatened me, but I yelled loudly and ran away. I spent two days in the library at Columbia, mostly in the reference rooms and stacks looking for books and citations and bibliographical sources or aids that I hadn’t seen in Madison. I met with Milt Rosen and Mort Scheer, the top leaders of the Progressive Labor Party. They shared information about similar revolutionary parties and groups in France that had been in correspondence with PL. I went to dinner with Laura and her roommate before leaving and we went to my old favorite NY bar, the West End bar, where Kerouac, Ginsberg, and other Beats used to hang. I was hoping Ginsberg would come walking in, but of course, he didn’t.

It was too expensive to fly directly to Paris in those days, so I flew into Brussels, Belgium. The flight was uneventful and I didn’t sleep much. In Brussels I changed money for Belgian francs, took a taxi to the train station and bought a ticket for Paris. In the station, I bought a roll and some coffee at a stand and waited for the train. The station seemed like something out of the 19th century. The trains looked different then those of the U.S. They were much older in design and were painted in drab colors. It was February and pretty cold, overcast and grey. Finally the train lumbered off to the south and within a short time we crossed into France and moved through the edge of the old coal mining area in France, the Nord and Pas-de-Calais. It was interesting to see signs with the names of cities and towns that I had been reading about: Lille, Valenciennes, Douai, Cambria.

The train arrived at the Gare du Nord. I descended the train and took in the large, noisy, busy station with people moving in all directions, loudspeaker messages booming in French, engines chugging and spewing steam, giant time schedules on the wall changing continually by means of mechanical numbers. I found a change station, bought some French francs, and found a pay phone that worked. I called Goldberg. He said, “Yes, well, bienvenue a Paris, camarade. Just grab a cab and tell them to take you to 13 Pont-aux-Choux. Then ring the bell and come on up.” I obeyed his directive and met an old hard-bitten Parisian cab driver who appeared to roll his eyes when I tried to speak French, but at least didn’t make me write down the address. Gare du Nord is located in the 10th, just north of the 3rd, so it didn’t take long to go down Boulevard Magenta to Place de la Republique and then south on Beaumarchais to a little street called Pont-aux-Choux, or the “bridge of cabbages.” The story is that Beaumarchais formed the outside wall of the city that separated ancient Paris from the rural areas. Apparently there was bridge over the wall that allowed farmers to bring their produce into the city. Goldberg’s address was 13. I tried to pay the cab driver by looking at the meter, but there were additional charges for being picked up at the station and the two bags of luggage. Then I gave him some francs that included a Belgian franc and this ticked him off. But soon he was on his way and I stood facing a tall wooden door with the number 13. I rang the bell and a concierge opened it. I told her I was here to see Professor Goldberg and she let me inside.

It was a good discussion, but it was getting late. Goldberg put me up in the small guest room of his flat that night because the “chambre du bonne” on the sixth floor was still occupied, but it would be ready the next evening. It was late, but I was still pretty wired, even though I hadn’t slept much, and asked if I could go outside walking for a while. He said fine, gave me a key (not a key like we think of a key, but a thick iron key that was about four to five inches long, and shaped like a long, peculiar skeleton key. I inserted it into the right front pocket of my jeans) and out I went into the Parisian night. It was around midnight. On the corner of Pont-aux Choux a small café was closing up. I walked a couple of blocks south to the Place Bastille, a big central big spire surrounded by a circle of four or five lanes of frenetic auto traffic. It was pretty hard to see where the ancient prison ever stood when they released all the prisoners during the revolutionary events of 1789. But I was invigorated by the activity on the street, the number of pedestrians, even at a late hour, the relative safeness of the space, the general feeling of the neighborhood of what was loosely called “the Marais”. Goldberg had described the Marais as “populaire” by which he explained he meant that it was populated and people-friendly, but not commercial or overtaken by tourists.

2

I awoke without knowing where I was, but then I remembered I was in Paris. I washed up and went into the apartment. Goldberg was writing, bent over a working table, surrounded by books, coffee cup, and ashtray half full. He poured me some coffee and brought some bread and jam. We walked to the Monoprix department store so I could buy some sheets and towels and then we walked up seven flights to the top floor. The room was small and triangular shaped. It had a couch that rolled out into a bed, a lamp, a chest, a desk, small book cabinet, and a sink. The unit had another great feature: a single French door opened to a small balcony that measured about 5 feet by three feet. The balcony looked out over the courtyard and beyond toward the west of Paris. As Goldberg noted, “You’ve got a great view of the rooftops of Paris. You know, Picasso developed his theories of cubism by studying the rooftops of Paris.” I didn’t know if that was true, but it sounded good. And the view was pleasant and not obscured since Paris has always maintained limits on how high buildings can be. I thought the room looked great, but I wondered about the bathroom. Of course it was a common toilet for all the inhabitants of the small maid’s rooms at the top floor. But it did not contain a toilet as we know it, but rather a “Turkish” style toilet that consisted simply of a slanted floor and a hole in the floor about 5” in diameter. The basic idea was to squat down over the hole and do your business. For men needing to urinate, it was quite easy because we could simply shoot (but responsibly) from above. It worked pretty well: they had the toilet paper hanging from the wall at approximately the right level. And it didn’t seem to matter that you didn’t have a seat to sit on, providing you weren’t planning a long term sit to read Le Monde Diplomatique or the latest essay from Sartre. Enough about such basic issues.

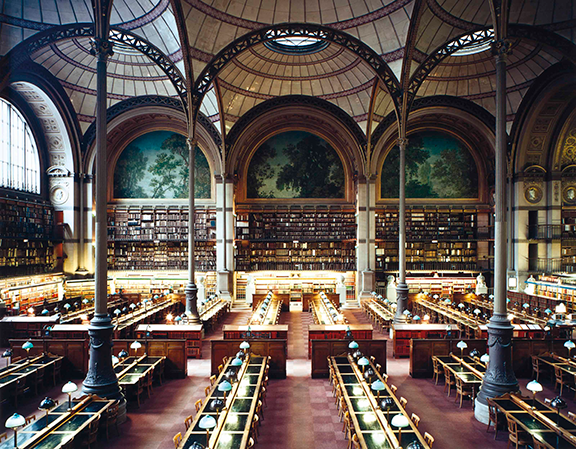

Biblioteque Nationale, Paris

I unpacked my stuff and joined Goldberg downstairs. He poured a small glass of wine and told me he was taking me to dinner that night, along with his friend, Randall, who I had not met. “Tonight, we’ll go together to dinner, but tomorrow I will throw you into Paris like a pollywog and you’ll have to find your own way.” That was fine with me. Randall arrived and we talked before heading off across Beaumarchais to an Alsatian restaurant located near the Oberkamp metro stop. It was during this dinner that I learned that the French generally served a salad near the end of the meal rather than as an appetizer; at first I thought it might be an Alsatian custom. After dinner we returned to Goldberg’s and he sat down and wrote out some instructions for working at the Biblioteque nationale (BN). This was necessary because of the extreme bureaucratization of the French libraries. I had brought the necessary documentation indicating that I was a Ph. D. candidate in good standing. It was letter signed by the Chancellor of the university and it had a big gold seal and a red ribbon to impress the French bureaucrats. Goldberg wrote out every step in longhand, using his black fountain pen, taking me through the interview process, and giving me directions to get to the correct room in the BN, and telling me what to do at each step of the way. At the time I thought Goldberg was going overboard, but it turned out he was right: one false move and you could be sent back to square one. He had suggested that I start with the grandes journaux, the daily newspapers that were on microfilm.

Armed with Goldberg’s written instructions and my little red “plan de Paris,” I proceded toward the BN. I had arrived in Paris in February, not exactly the best time of the year. It was cold, rainy and damp and I had to purchase an umbrella. From Pont-au-choux I walked up Rue de Bretagne, then Rue Reamur and Septembre 4th. The BN is located in the 2nd arrondissement, so it is just adjacent to the Marais. It took about 25 minutes to walk. I showed my certificate to the guard and was allowed in the courtyard. Inside the BN I went to an office for an interview with a lady who had the power to let me use the library. The interview was brief, but I had to sign off that I understood all the rules of the library. After some time, I was issued a card and allowed to go the big room where the grandes journaux were located. I looked up the newspapers in the card catalogue filled out some forms to receive them. I approached a tall desk where a librarian sat high in the air, far above the patrons below. I reached up to turn in my forms. She picked them up, perused them, and frowned darkly. “You did not fill these out properly,” she said (I thought she said; I really didn’t understand, but I knew I had done something wrong). She returned them from on high. I went back to the card catalogue to figure out what I had done wrong. I had to look up some words in the dictionary to see what the exact meaning of the words used in the form. I filled out new forms once more and turned them in, but alas, there still was something wrong and I had to redo them a third time. Then I learned that you could only make two requests at a time and they could include only one reel of microfilm. I waited for about 30 minutes for the microfilm to arrive. Finally it did, and I hooked it up to the reader and started to read.

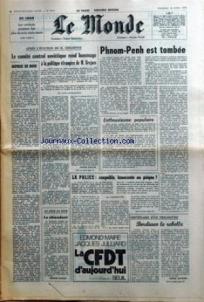

Le Monde 1975

The next three weeks I read newspapers covering the period form 1945 to 1949, including Le Monde, L’Humanite, Combat, Le Populaire, and others. Despite the inefficient bureaucracy, I was able to come up with a decent work routine. The first day I went to a small café across the street for lunch, but my budget would not allow such luxuries to continue for long. I bought one of those cheap cloth book bags to pack my papers and dictionary and on my way to the BN I would stop for a coffee and buy a baguette and some cheese. At lunch I would sit outside the library and eat bread and cheese and then buy a coffee from the machine in the basement of the BN. There were several students working in the library and one day a young woman sitting across from me was wearing a University of Wisconsin sweatshirt. Glad to see someone from the Badger state, I said, “You’re a long way from Wisconsin.” She looked at me like I was crazy and I had a hard time trying to explain what I meant. There were other embarrassments, as usual involving language problems. In one case, when I was returning a book to the librarian because I had finished it, I handed it to the gentlemen and announced “I am finished with this” by saying “Je suis terminee avec ca” and receiving no response from him. After doing this a few times, I noticed that after I made my little statement he added, “Vous avez terminee”, with a special empasis on the first two words. Then I understood my grammatical error: I should have said “J’ai terminee” instead “Je suis terminee.” I realized how ignorant I sounded saying “I be finished with this.”

I did meet a few people working at the BN. One was a history student who was studying under Marc Ferro, a famous French historian. He was working on a project involving film in the 1930s and 1940s. His name was Jean-Philippe and he was around my age. After working at the BN one Friday afternoon he invited me to come to a café with him to meet some friends. We went to a place located near Les Halles. A few of his friends arrived until there were five or six of us. I couldn’t keep up with their French and just listened trying to figure out what was going on. I found that I could understand best if they were discussing politics or history, since that is what I was reading and also because so many of the political terms are the same in English and French. They asked me if I wanted to get something to eat and I agreed. We walked north up Strasbourg-St. Denis to a cavernous place called Restaurant Julien. It featured long tables with paper tablecloths. Diners sat in rows of twenty or so people on each side of the table. To eat with someone required going down a different row and ending up across from each other. The prices were very reasonable and I opted for the less expensive items: a hardboiled egg and mayonnaise as an appetizer, a piece of chicken and some peas. We ordered cheap red wine and I warmed up to the situation, even though I kept my comments to a minimum and concentrated on trying to understand the conversation. There was one woman in the group and they were more or less political. They asked me about politics in the states and, because I didn’t really want to talk that much in French, I turned it around and asked what their perception was of contemporary American politics. It was then that I first encountered the reality I saw again and again in France. Despite their political sophistication, they tended to harbor some strong and not very accurate stereotypes about American society and politics. And they often had a tendency to put down American leftists as rather rootless and hopelessly isolated voices in the wilderness as opposed the French movement with its long tradition and large socialist, communist, and gauchiste parties. The dinner at Julien was stimulating and fun for me because I hadn’t gone out to dinner with anyone for about two weeks. I also learned about an interesting meeting that was going to take place in Lens, in the heart of the coal mining area of the Pas-de-Calais. An explosion in the mines had killed several miners a few months previously and a giant tribunal des mineurs had been planned to look into the causes of the accident and what could be done in the future.

I hadn’t seen Goldberg for two weeks. I had accepted what he said about being a pollywog and had been swimming in my own river. And wet it was in Paris. It seemed like it rained every day in February, March and part of April. It got dark early. I would leave the BN around 5:15 p.m. and it would be night. On my way out of the courtyard I would buy a copy of Le Monde and take it home to read. I was pretty lonely, though. I really missed April and Rachael, but I also missed daily conversations and discussions. Back in Madison I was the head of a group of about 50 wild-eyed radicals and a teaching assistant for hundreds. I felt particularly weak in the face of the language barrier. Randall and I started a French class at Alliance Francaise, but I dropped out after two sessions. With the exception of waiters at cafes or clerks in a boulangerie, I talked to no one. One afternoon as I was returning from the BN and walking down Beaumarchais I saw Goldberg sitting in the Café Balto. Of course he was at work, writing and reading with an empty espresso and his familiar cigarettes. Although I didn’t want to bother him, I thought I’d pop in and say hello. I sat down across from him: “Hello, Harvey, what are you reading?” He looked up with tired eyes slowly from his book (on German social-democacy, 1917-1923) and put down his fountain pen. “You know, Darryl, when you really look at the situation closely, the people really did prefer reform to revolution.” This was a bit of a shocking statement from Goldberg, the notorious leftist professor, the viscerally radical iconoclast who seldom compromised. I didn’t really know how to react, but I told him, somewhat opportunistically, that I was reaching somewhat similar conclusions in my own research for the last two weeks. That started a good discussion. I ordered a coffee and started telling him about my findings. I knew Goldberg enough to know that it was important for me to make good use of my time with him. The more I put propositions and ideas in front of him, the more I learned from his responses. Not just how he reacted to my ideas (which was generally positive), but other information such as certain writers or books that shed light on that particular issue. If I didn’t set the agenda around my research, however, the conversation would soon revolve around Goldberg, his thoughts, his stories, etc. Once I got through my stuff I’d listen to his stories. Goldberg was waiting to meet a friend, Jean Gordon, a British graduate student in history who lived in Paris. He introduced her to me. She was around my age, perhaps younger. She had dark hair and it had been colored by henna, the big fad in France in those days. Goldberg asked me about my living arrangements upstairs and Jean suggested that she had a hotplate that I could use.

3

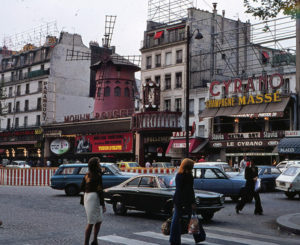

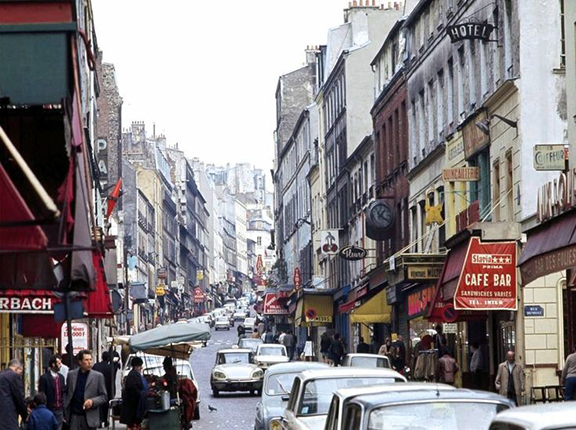

The next day I went to Jean’s to get the hotplate. She lived in the 5th on Rue Tournefort, one block west of the charming Rue Mouffetard, the narrow cobblestone street of cute little shops and restaurants that winds its way down a hill for several blocks from the Pantheon to Les Gobelins. Jean was living with a French man named Bernard, who was a member of the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) and some kind of academic (he was about 10 years older than Jean).

The Rue Mouffetard in Paris in the 1970s

I was happy to get the hotplate. I couldn’t afford to eat in restaurants so I had been dining on street food or things I didn’t need to heat up, like cheese, sausage, bread. On the way home I purchased a couple of pans and some silverware and other stuff so I could cook at home. Over the next few months I made good use of the hot plate as I lived on a diet of pasta, dried soups, and ramen noodles. One Sunday afternoon my friend and fellow Ph.D. candidate Gary Cross showed up at my door. Like me, Gary was a Goldberg student. He was working on immigrant workers in France, a great topic that Gary turned into his first of nine books. Gary had been to France before and he knew more than I did about getting around. As usual, it was raining when Gary showed up. I had a bottle of red wine available, so we sat around and talked about our work. We could go on for hours in these discussions that had really begun several years ago when we first became friends. Another graduate student from Wisconsin, Mary Reardon, came by with Gary on a Sunday and we took off for various museums. We started at the Jeu de Palme to see the impressionists and we went to the Louvre, which was pretty boring. On another Sunday we visited the Mur des federes, the wall inside the Pere Lachaise cemetery where the last members of the Paris Commune were shot and killed in 1871 after the Commune was crushed. The next day Gary met me at the BN and we went to one of the student restaurants (located east of the Bastille, near the Ledru-Rollin metro stop) so Gary could show me how we could eat there for next to nothing. Students could buy CROUS cards for inexpensive meals at designated student restaurants. Of course we weren’t students, so we had to find a student willing to sell us a ticket. “Pardon, est-ce que vous-avez un billet a vendre?” I tried it and it was pretty easy. For me, girls were easier to approach than men. The food was served cafeteria style and it was relatively good. The portions were sizable. After that I used the student restaurants whenever I could. One problem was that none of the restaurants were located near the BN or the Archives Nationale (another place where I worked). When I worked at the Bureau de documentation internationale et contemporaine in Nanterre, to the west of Paris on the RER, I found a very good student restaurant. There was another one located on Franklin Delano Roosevelt Avenue near the Champs Elysee. The other problem occurred when there were other non-students like me who were trying to get tickets. I usually waited for them to succeed before trying my luck.

Money was always an issue and I found I was almost always hungry. I would walk past restaurants and patisseries and smell the delicious aromas, feeling sorry for myself. In the morning I would make coffee in my little Melitta pot, then go down to the street to buy a long baguette. I would eat part of the baguette with strawberry jam for breakfast and I would take the baguette with me to the library. At lunch I would buy some cheese or sausage and eat it sitting outside. At night I would take what was left of the baguette and eat it with my dinner in my little garret. One of the reason I watched my money was because I was finding interesting books to buy. After dinner I would go outside for long walks, frequently to several bookstores, especially the FNAC (which at that time was owned by the Trotskyist Ligue Communiste) or the Maspero (a family of old radicals, Goldberg knew them) store located in the Latin Quarter. To me it was a big deal to buy a book; I would ponder which one I wanted most. Then I would take it home and read it late into the night. I also developed an interesting kind of game to accompany the long night time walks I took in the streets of Paris. Like most visitors to Paris I carried my little red Plan wherever I went because it was so handy. But sometimes I would purposely keep my Plan in my pocket and just walk along with no regard to where I was heading. The streets are so irregular that it was easy to start walking on direction and soon end up going in the opposite direction. I would walk for an hour or so without knowing where I was. Then I would look around for a metro stop with its giant map to see exactly where I had ended up. It was often surprising to see how far I had gone. One late night while I was walking back to the Pont-aux-Choux I saw a young lady standing on the corner near Rue St. Gilles and she seemed to be asking me something. I stepped closer and heard her say, “Ce soir, monsieur?” At first I didn’t understand, but then I figured it out and answered, “Non, pas ce soir, madamoiselle.”

I celebrated my 28th birthday in Paris, but it was a pretty lonely celebration. It was a drizzly, grey Sunday and the libraries and archives were closed. I slept later than usual and got up and made coffee. I folded last night’s Le Monde under my arm and stashed a few of those blue, air mail letter/envelopes that have the postage already on them into my book bag. I walked a block west and then south on Rue de Turenne until I reached the very pleasant Place des Vosges. I sat on a bench and took in the sights. To me this is a splendid place to sit and watch and read and write letters. Place des Vosges is not large park (about two blocks) and it has no grass (gravel walkways and ground cover, but great shady trees and shrubs). I watched the little kids with their parents and grandparents and thought about home. I wrote letters to April and Rachael, describing the park and the kids and how I wanted to see them and was lonely for home. My writing was interrupted by rain and I popped into a corner café and splurged on some eggs and sausage and a café au lait. I finished my letters and dropped them into the mail shoot in the café.

Returning home, I saw a note on my door from Goldberg, asking me to see him in the late afternoon and go to dinner. I met him at about 6 p.m. He offered me some crackers, feta cheese, and a small glass of retsina wine (Goldberg was not a drinker, apart from a social glass of wine. “I’m not much into spirits,” he said). Randall was not around and we walked over to a Vietnamese restaurant near the Rue du Temple. I had seen this small, attractive restaurant and I had become somewhat acquainted to its fine-smelling food as I walked past in the evenings on my way to my hot-plate. I was glad Goldberg had invited me because I knew it would be a good meal and he would pay. Goldberg knew the family that owned the restaurant. He knew quite a few Vietnamese. Goldberg had been active in the anti-war movement in the U.S., but in France he was active in a unique way: he was part of the first group of American citizens to meet with the North Vietnamese to discuss peace in 1965, during the expansion of the war in Vietnam. Of course the meeting took place in Paris, where a large Vietnamese community resided. My old friend Diana Johnson had also been involved. These activities came to the attention of the French police and Goldberg was warned not to get involved in political activities. The food was great, especially for a cold, grey day: spicy Vietnamese soup to begin, beer from China, a dish of egg noodles, beef and greens, and bunch of other entres. The lady who ran the establishment came out and sat with us. She introduced her 18-year old son and he sat with us for a while. It was really great and I ate a lot. They kept bringing us out food as soon as we had finished what was on the table. Goldberg always ate very modestly, but I could finish up every dish. So the food kept coming, as if by magic. Even though Goldberg was thin as a rail, in his early days as a student in Madison, he was quite obese. I was also lean at 28 years of age, but I was hungry in Paris and I could eat for two or more. We had a wonderful Vietnamese dinner that night.

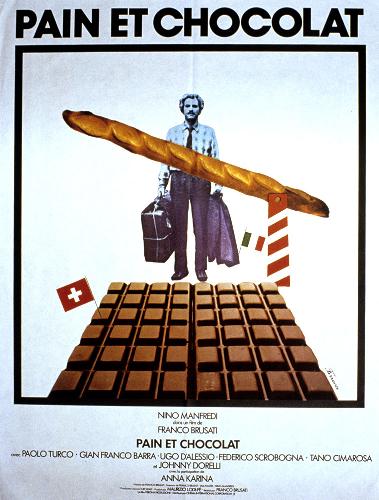

Paris, 1975

Goldberg gave me an invitation to Jean Gordon’s party next weekend. He couldn’t go because he would be out of town. The party had a theme: “Il etait a Hollywood” (“It Happened in Hollywood,” a film that had just been released). She said she wanted to encourage people to dress like a Hollywood character. The group included several of Jean’s co-workers at a large language program in Paris. About 25 people showed up and only a few were in what seemed to be costumes. (I didn’t have any costumes available and that day I had a scheduled a 4 p.m.meeting and interview with Gilbert Sauchel, editor of a monthly journal called Afrique-Asia and activist in the 1940s and 1950s. We started at Gilbert’s office, located near Les Halles, and then moved to a nearly café.) I was wearing the same clothes I wore almost everyday: blue jeans, rock boots, a light blue work shirt and the beat-up old leather bomber jacket I had purchased for $10 at Marilyn Goodman’s used clothing store, Cheap Thrills, in 1970. I didn’t arrive until around 9 p.m. Jean had cooked up a big cous-cous for everyone, and there was chicken and lamb and charcuterie and red wine. I was pretty hungry. After the cous-cous, Jean brought out a big salad and of course later there was bread and cheese. It was a festive event and I enjoyed meeting Jean’s friends. They were mostly around my age and included Monique Bonfils (Elizabeth Taylor), Daniel, Isabelle Vellay (Olivier Newton-John in “Grease”), Sylvette, and Francis Feely (a Goldberg student a few years older than I who was working on his dissertation and lived in the racey Pigalle district). Asked about my costume, I suggested that I was Marlon Brando in “The Wild Ones”. Because there were many English-speaking people at the party, it was easier for me to follow the conversations and be involved. Even though the party was “in French” people moved back and forth so it was easy to pick up common phrases and understand how to use them. Also, I found that the English-speakers’ French was much easier to comprehend then the French Francais. And it was easy to get clarification on something without feeling like an idiot since, thankfully, most of the people there were language teachers. I learned a lot, just talking to people. And it was very interesting politically for me because many of the people were involved in one way or another. Isabelle’s brother Marc Vellay was a leader in one of the groups that PL had communicated with and she said he would like to meet me. Francis Feely, originally from Texas but in graduate school at Wisconsin, was supposed to be working on a dissertation on French socialism from 1890 to 1914, but in reality Francis was hanging out in Paris and writing a kind of sociological study of the (apparently growing) transvestite community in the Pigalle district. Jean’s friend Bernard seemed a bit distant, partly on political grounds: his group was aligned with one of our competitors in the U.S., the Revolutionary Union, and he seemed dogmatic to me. The party was heating up, but the host had run out of wine. One of Jean’s friend whose name I forget took up a quick collection and went out to replenish our drinks.

This was a typical, fun party for twenty-somethings, much like the usual parties in America. But then I noticed an interesting dynamic begin to occur as the clock moved closer to 11:55 p.m.—Metro closing time. It meant that everyone at the party (obviously no one had driven a car to Jean’s party) had to decide if they were going to stay at the party or if they were going to leave in order to catch the metro. Or, if they lived too far away, did they have enough money to take a taxi? The looming Metro deadline also meant that those who were interesting in pairing off with anyone needed to negotiate those plans in quick order. It was interesting to watch this ritual unfold before my eyes. It didn’t really concern me since I lived relatively nearby. Someone brought out a guitar and started playing a French song. Someone else produced some hashish and decided to share it with the remaining nine or ten who disregarded the Metro’s departure. A few people played songs, most French songs and some political songs. Then one of the men played a not-so-good version of Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” and most of the group chimed in on the vocals. But they lost track of the lyrics in the second or third verse and I put them back on track for the rest of the song. Then they asked me if I could play Dylan songs and I replied yes. I hadn’t played a guitar since leaving Madison, so it was great to play it. I played a few Dylan songs and they liked it a lot and I answered, yes, I was from Minnesota too, and yes, I had seen Dylan in concert (in 1967: Dylan didn’t tour after his motorcycle accident in 1967 until 1976) and yes, I did know “Tangled up in Blue” from “Blood on the Tracks.” I played it and it felt great and one of them said, “Alors, c’est pas vrai, c’est exactament comme Dylan!”, but I turned over the guitar to the others, to be polite and because I didn’t want to look like a show-off. In fact, I really wanted to keep playing because I enjoyed it so much—with or without the audience. The party continued until about 3:30 a.m when Jean announced she was turning in. We left her flat and walked a few blocks down the Mouffetard, which was still somewhat “populaire” with smatterings of people still on the street. We walked toward the university at Jussieu and then past the zoological department at the Jardin des Plants. We could hear the sounds of animals in the zoo and it sounded incongruous against the dead middle of the night sounds urban of Paris. Someone yelled, “Let the animals out of the zoo! Down with all zoos!” which drew a lot of laughs. We crashed at Monique’s flat, located near the Gare d’Austerlitz on the eastern edge of the 5th. I had a couch in the library. I slept for a few hours and woke up, put on my boots, and walked back to the Pont-aux-Choux, passing through the crowded Sunday morning market on Rue du Rivoli.

4

Goldberg had given me a list of scholars and intellectuals that I should meet. I spent an afternoon with Daniel Hemery at Jussieu. He is a sociologist who grew up in the north of France and was a child during the big coal strikes. Daniel described growing up at a time when people identified an event’s chronology by whether it occurred before or after the big coal strikes of 1947 and 1948. He gave me a number of suggestions of people to read or meet. Through Goldberg I also connected with Diana Johnstone, my old friend from the radical days at the University of Minnesota, where she was a professor of French and Italian. Diana was now a journalist who worked as a night editor for Agence-France Presse. She was also the European editor for one of our weekly journals, In These Times. She invited me to dinner at her place near Montparnasse and we were joined by another more former U of Minnesota colleague, Tita Viviana and her husband, Paolo. Paolo was a physicist and a member of the Italian Communist Party. Diana started work at 11 p.m. so we walked with her over to the offices of Agence-France Press. She took us inside to the wire service area to see the latest information coming in from Vietnam. The Viet Cong and the North Vietmamese were reclaiming South Vietnam and the Americans were pulling out. It was interesting to see all the detailed reports emanating from the front line rolling off the wire service. It made me think about the disparity between information coming from Vietnam and information published by the American press.

A few weeks later Goldberg, Diana and I went to a public meeting at the legendary meeting house, La Mutualite. The meeting was focused on the latest intellectual rage sweeping France, the so-called “new philosophers.” There was a lot of milling around before the event (which began fashionably late) and they introduced me to Michel Foucault who was overweight, bald and not particularly pleasant. Goldberg knew him from way back, but more recently he had been talking with Foucault about his work on prison systems. Goldberg was doing research on political repression in France. Diana was writing weekly stories on these new philosophers, Glucksman and Levy. They were former leftists who had suddenly discovered that there were bad things in the Soviet Union and other regimes and, therefore, we should all move to the right. As Diana noted walking out of the meeting after lot of windy speeches, “they are neither philosophers nor new.” The Mutualite was a big beautiful hall and the crowd, which numbered several hundred, couldn’t begin to fill it up. But it was exciting to be there, to see the inside of the famous hall. In my research I had come across several important mass meetings that had taken place at the Mutualite and I was glad to be able to say I had been there.

Monique left a note in my mailbox inviting me to a dinner party on Saturday night and asking if I would be willing to play some songs for the group. She said she had a guitar I could use. All I had to do was show up. Always up for a good (free) meal, I thought it was pretty fine idea. I went, the food was good, I played Monique’s guitar and everyone had a nice time. Monique told me I could keep the guitar during my stay in Paris, which was very generous of her because I greatly enjoyed using it and I wrote a couple of songs during this period. The guitar also paved the way to a number of free dinners from various people who had heard me play.

One day Goldberg asked me to go with him to a Saturday meeting that he had called for academics and students to organize a conference in Paris called “L’Histoire: Pour Quoi?” It was a pretty interesting gathering including people whose names I had seen before. Goldberg ran the meeting and did a very good job drawing out their ideas, listening to their views, and writing notes on a blackboard. The meeting took two hours and Goldberg had everyone signed up for committees and new meeting dates were set. It was pretty interesting, but I didn’t get involved, having enough to worry about. I did however, attend the conference when it took place several weeks later. It succeeded in bringing out a few hundred people. Because of my proximity to Goldberg I was able to hang out with the top organizers, especially at lunch where we retired to a nearby restaurant and filled up a big table in a separate room. From the people there I received some leads of people to look up when I traveled north, including the author of Mineurs en Lutte, Andre Theret, who lived in the Pas-de-Calais and the address and phone for Etienne Dejonghe, the historian who had written the most about the mining region.

By the time it was April I had expanded my research from the BN and the AN to include several libraries and research center all around the city. Every new library meant visiting another district of Paris and spending a few days or more working in the library, drinking coffee and reading in the nearby cafes, having lunch in the neighborhood parks. I especially liked the area around Place d’Italie where the Communist Party archives were housed. The Communist officials were quite helpful to me. They gave me access to a lot of material. They had bound periodicals of all the French Left periodicals organized in a research room that was comfortable and easy to work in. They had a pretty good library and you could get Xerox copies, a big technological breakthrough at the time. They also had an interesting big collection of pamphlets, posters, and leaflets.

Then it was May Day and of course, all the libraries were closed. These closures were painful to me because I couldn’t get any research work done. There were many closures for holidays since the French have so many national holidays. Jean’s group was planning on marching in the May Day march and Goldberg and I were told to report at a café located near the Nation metro stop. Their union was affiliated with the CFDT. Thousands of people participated in this march through Paris on a bright sunny day. It was so large that you didn’t participate by going to a point where the whole thing began. Instead, it began and groups gathered along the way and fell into line. There were a lot of police, but the march was orderly since the big parties and unions usually didn’t let the gauchistes and anarchists participate. There was a large contingent of several thousand Vietnamese and it was very significant since in the past few days the U.S. finally pulled all our troops out of Vietnam. Viewing this as the end of the Vietnam war (one which was initiated, of course by the French long before the Americans got involved), the march had an optimistic feel to it, as if something important had actually been accomplished. We marched along the streets, thirty or forty people abreast. People lined the streets and looked out of windows. It was the most upbeat march I ever attended, with the possible exception of when Nixon resigned and the Madison Left spontaneously gathered at the state capitol and began marching endlessly around the entire square.

When we reached the Clichy metro stop, we peeled off from the march and went to Francis’ third floor flat in Pigalle. I had visited Pigalle before because Isabelle lived a block from Francis. Pigalle was where the dancing girls, sex shops, dirty films, and other racy activities took place. We climbed up the stairs to Francis’ place. He had access to a rooftop area that overlooked the streets below. Unlike my tiny patio, this space was enough for several people to sit and stand. Francis brought out some bread and cheese and wine and beer. Even though he was a Goldberg student, he was a few years older than I and I had never met him in Madison and I had never talked much with him. Francis poured us some pastis over ice. He told me about growing up in rural Texas and I told him about northern Minnesota. We traded stories and the discussion quickly began to take a nostalgic tone as we talked about such non-French things as cheeseburgers and beer, cars and trucks, playing football, drive in movies, Madison in the fall, Door County in the summer. I hadn’t talked to someone like Francis for a long time. He was pretty wild and had this connection the transvestite community, whatever that was. One of his subjects (?), Michel, came to the party dressed as Barbara and thus was introduced as Michel-Barbara. She arrived quite intoxicated and went around to meet everyone. Wouldn’t you know that she took a liking to me? Fortunately my French was so poor that I couldn’t communicate well and she drifted off. Later, as the party was moving forward, she started to do a little strip-tease that, frankly, wasn’t that exciting. Fortunately, we weren’t forced to see her breasts or penis; she stopped just in time. Francis sent someone to accompany Michel-Barbara to a more appropriate place. I returned to the rooftop deck and listened to Francis go on about his theories regarding transvestisme. I asked him to tell me if there was a point where research turned into voyeurism. He didn’t like the question, but admitted it was valid. I asked him if he had ever tried cross dressing and he laughed and said no. “I live in Pigalle and I encountered this community and it’s interesting to me.” I took him at his word. The sun was beginning to drop as we gazed over the Parisian rooftops and it was quite beautiful. May was here and the rains of the spring had given way to the sun of the summer in Paris. I was ready to make my trip to the north.

5

Several weeks later, on a warm Saturday I walked down crowded Rue de Rivoli near St. Paul. My research in the north was over and I would be heading home soon. I made several trips to the northern area to visit archives and libraries and to interview people in Lille, Arras, Lens, and Lievin. I had taken two boxes of books to the post office to ship back to Madison. As I walked along the street I was aware that a young couple were heading toward me. It was only when I looked closely at their faces that I realized I was seeing my old college roommate, Dave Donatelle and his wife, Sandi. What a surprise! In Minneapolis Dave and I and others shared an apartment on the west bank in 1968. His father had been our family doctor when I was a kid. Dave had majored in Art and I hadn’t seen him since 1972. It turned out that Dave was going to medical school in Paris and Sandi was working at a clothing and perfume shop. We went back to their place on the L’Ile St. Louis on the Quai de Bethune and then took a walk to a corner brasserie for some food and drink. We talked over coffee for an hour or so. Then I left Dave and Sandi and headed back to the Pont-aux-Choux.

The River Seine, Paris

Walking back on the next to the last day in Paris I felt that the time I had spent in France had been somewhat transforming. I really felt that I was somehow different for the experience. I even looked different as I saw my reflection in storefront windows. My hair had grown longer and was touching my shoulders. My old rock boots had been replaced by a pair of inexpensive wooden clogs. Someone had given me a “bleu,” those dark blue cotton jackets worn by working class Frenchmen, to replace my old leather jacket. My French had improved considerably and my choice of cigarettes had changed from Marlboros to Gaulloises. I no longer had difficulty filling out forms for the library or the post office. I knew the Metro quite well and could use the phones. When I interacted with people, they no longer assumed I was an American (not that I would have ever denied it) and sometimes they asked if I was Swedish or Dutch or Canadian. A song I had written, “Left Bank Blues,” summed it my sentiments: “I’m not the same.”

The sun was receding in the west, illuminating Paris in spectacular ways. I bought a copy of Le Monde and stopped at a sidewalk café that faced the Seine. I ordered a pastis. The waiter dropped ice in the glass and added the liqueur and I watched the clear liquid turn milky white.

By Darryl Holter

For Julia Holter

–

Photo By Barry Lewis (April In Paris – 12) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Photos by www.galenfrysinger.com

Photo by www.pinterest.com/vintageseekers

Photo by www.aparisguide.com/seine/

Follow Darryl Holter Music

Recent Posts

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur. Darryl Holter is also a historian who has written on Woody Guthrie and a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.