About Darryl Holter

About Darryl Holter

Country, Blues and Folk Traditions

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As a child, his early influences were Elvis and Johnny Cash, then Bob Dylan, then the folk-rock and country-rock. His current brand of Americana Music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events. In 2008 he formed 213 Music and launched his first self-titled album of original songs. Two years later he released “West Bank Gone,” an album that highlighted the West Bank (of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis) music scene in the 1970s. Besides his music, Holter has worked as an academic, a labor leader, an urban revitalization planner, and an entrepreneur.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Music has always been in Darry Holter’s life. Having grown up in Minneapolis, the oldest of four, his father listened to country western music on the radio and had taught himself how to play the guitar while serving in the Army Air Corps. When Holter was 6 his dad bought him his first guitar. His father also gave him sheet music from songs they had listed to on the radio. Having been familiar with the tunes, following along on the guitar came naturally.

Darryl was in the 4th grade when he first heard Elvis Presley. He immediately went to the record store and bought “Heartbreak Hotel” and “I Was the One” and played them over and over. Holter soon played community fairs and charity shows all around the state with a show sponsored by a charity organization that my father belonged to. Rock music was still new, so Elvis and Gene Vincent songs were kept at home. At the shows Darryl played they wanted songs like “Cattle Call” and “I Really Don’t Want to Know.”

When Darryl was about 12 a friend who had a sister at the University of Minnesota played him the first Bob Dylan album. Holter found it exciting: basic, with lyrics worth listening to, as opposed to the suburbanized country music he heard on the radio. Around the time of his confirmation, age 14, there was a young (Lutheran) pastor who had brought a genuine folk-singer to lead a little hootenanny around the campfire. They were all sitting around singings songs that had come out of the civil rights movement in the South: “Kumbaya” and “We Shall Overcome,” etc. When they passed the guitar to young Darryl, he played Dylan’s version of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” The response was positive and he came away more interested in the folk scene.

I remember the controversy when Dylan went electric. A lot of folks were upset, but not me. – Darryl Holter

The Music

Holter went to the University of Minnesota for college and as the Vietnam war escalated, he became involved in the anti-war movement. This led to protest songs by people like Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs. In graduate school, in Madison, Wisconsin, he worked as a teaching assistant and got involved in organizing a union. Soon he was doing old labor union songs and writing a few of his own. He worked for the AFL-CIO in Wisconsin and played in a few concerts with Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Joe Glazer, and a close friend from Milwaukee, Larry Penn. He played at picket lines and rallies from one end of the state to the other. Holter wrote about 40 songs over the course of several years. Taped on a little cassette and then tossed into a drawer. He wrote 40 songs that no one had ever heard.

When I moved to LA I began to move my music away from politics and toward what might be called more reflective songs with themes of love and loss, memory and imagination, humor and noir. – Darryl Holter

Then finally he decided to take the best songs and recorded a CD. Holter teamed up with Ben Wendel and together they selected the ones to record. As they neared the end of the recording sessions, Darryl had the urge to write new material. Out of this desire came “Don’t Touch My Chevy” and “Blues in Your Pocket” and they added them to his first album.

I met Ben Wendel and we hit it off well. He listened to about 20 of my songs and we selected the ones for the CD. Rehearsals at Local 47 were really fun for me because I had never heard any of my songs with anyone playing except me. The songs are like my little children and I could see them developing before my eyes (and my ears) under the direction of Ben and the skills of Tim, Nate, Billy, and later Greg, Nels, and Julia. Recording at Capitol Records in Hollywood was an experience to remember for me. As we neared the end of the recording sessions, I experienced this strange desire to write new songs. It was as if this first group of songs was going out the door and a new batch needed to be created. – Darryl Holter

Darryl continues to record having recently released his new Roots & Branches album in 2018.

Author and Historian

Darryl Holter is a historian, former automobile dealer, and author. In addition to co-authoring Driving Force, his books include The Battle for Coal: Mineworkers and the Politics of Nationalization in France, Workers and Unions in Wisconsin: A Labor History, and Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941.

Darryl Holter has taught history at the University of Wisconsin and UCLA and is an adjunct professor at USC. Holter is the CEO of the Shammas Group, a family-owned group of automobile dealerships and commercial property located in Downtown Los Angeles. He is the founding chairman of the Figueroa Corridor Business Improvement District, begun in 1998, which led the revitalization of Figueroa Street from the Staples Center to USC and Expo Park. He is a singer-songwriter and has produced four critically acclaimed albums since 2008, most recently Roots & Branches (2018 213 Music).

He is a member of Professional Musicians Local 47. In 2014, Holter, along with Bert Deixler, purchased Chevalier’s Books, the oldest independent book store in Los Angeles, to save it from closing. They have revitalized the store and view it as an important link in the city’s intellectual infrastructure. Holter is also a contributor to The Los Angeles Review of Books.

More From Darryl Holter

Q&A with Author Darryl Holter

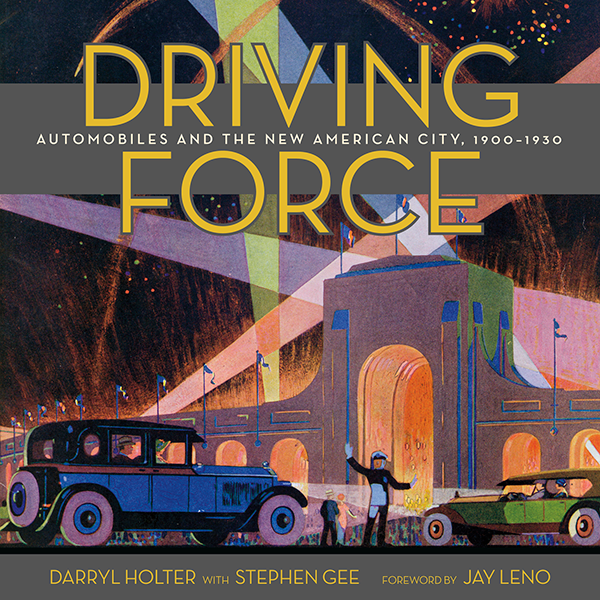

Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City, 1900-1930

Why is the book significant?

This is the first book to explain how and why Los Angeles became so obsessed with cars by highlighting the entrepreneurs who convinced people they were a necessity and not a luxury. It was dealers and not manufacturers who introduced cars to the city. The car-centric lifestyle they championed still defines Los Angeles a century later. What makes this story particularly interesting is that unlike other major cities such as New York, Chicago and Philadelphia, Los Angeles and the automobile came of age at the same time. Cars offered unprecedented mobility and allowed the city to expand to places the rail lines didn’t reach.

How did the book come about?

I was sitting in my office at Felix Chevrolet one afternoon and I got a phone call from the California New Car Dealers Association, our trade group in Sacramento, and they said, ‘Darryl we were moving some things around and we found some boxes with this old material in it that we were going to throw away and someone said you better take a look at it.’ I went up to Sacramento and I found the minutes of the meetings of the Motor Car Dealers Association of Los Angeles, 1905-1920. These are the type of primary documents that historians love to find.

How important were Los Angeles car dealers to the automobile industry?

Los Angeles quickly became one of the biggest markets for cars in the United States. There were more cars per capita in Southern California for most of the period covered in the book (1900-1930) than any other part of the country. The pleasant weather and varied terrain encouraged motoring and importantly allowed dealers to sell cars year-round. Powerful city retailers like Earle C. Anthony and Don Lee became statewide distributors for their brands. Ralph Hamlin was the most successful Franklin distributor in the nation and when he demanded the manufacturer modify their cars to his specifications they listened.

What characteristics did early automobile dealers share?

Many early Los Angeles automobile retailers began selling bicycles before transitioning to selling cars. They had a basic mechanical understanding of how they worked and took a chance on a start-up industry that almost all banks considered a fad at best. A good example is the city’s first car dealer William K. Cowan, who operated the Rambler Bicycle Shop on South Spring Street before making the city’s first car sale, a Waverley Runabout in 1899. Ralph Hamlin also operated a bicycle shop on Main Street before he began selling Franklin automobiles in 1905.

Today Tesla sells cars without using dealerships. Why did dealerships become the main link between manufacturers and customers?

Early automobile manufactures lacked the funds to build a network of retail facilities. They experimented with middlemen, agents and traveling salesmen but ultimately had to rely on local entrepreneurs to sell their product. Carmakers also relied on dealers to provide, through deposits, the working capital they needed to assemble cars. As no factory warranties existed dealers also assumed the responsibility for providing service and repairs. When the market for expensive cars tightened dealers changed the way cars were sold by experimenting with credit sales by accepting down payments and deferred payments.

How important were women to the early car business?

Although women were underrepresented on the sales floor they were incredibly important to the design and marketing of early cars. Many of the innovations that they demanded, such as windshields, electric ignition switches, glove compartments and upholstered seating would become standard features. Women also particularly liked electric vehicles because they weren’t noisy, and they didn’t smell or have exhausts. Los Angeles would lead the nation in terms of the number of women motorists and local dealers competed to earn their business.

How does this book reflect the diversity of Los Angeles?

The automobile pioneers included in the book came from vastly different backgrounds. We shine a light on Mexican American dealer Winslow B. Felix who used Felix the Cat to promote his Los Angeles Chevrolet agency; Ygnacio R. Del Valle who grew up in one of California’s prominent pioneer families before selling Brush cars, promoted as costing less than it costs to keep a horse; Tommy Pillow Jr., one of the first African-Americans to build and race cars in Los Angeles; James S. Conwell who juggled selling cars with his role as President of the Los Angeles City Council; and Sybil C. Geary who transformed the Automobile Club of Southern California into the largest motor club in the world.

How did Los Angeles car dealers use their influence?

While some early dealers and automobile brands failed, others went on to become rich and powerful. Earle C. Anthony, who represented Packard, would form KFI radio and KFI-TV (now K-CAL). He also championed better roads and bridges across the San Francisco Bay.

Paul G. Hoffman, who sold Studebaker cars, launched KNX radio primarily to promote his car business. He would later be recruited by President Harry Truman to help rebuild Europe after World War II. Don Lee, who represented Cadillac, would operate KFRC radio in San Francisco and KHJ in Los Angeles. He would later launch an experimental TV station that later became KCBS-TV. R. Leslie Kelley, launched the Kelley Kar Company and also the Kelley Blue Book, now the industry standard for accessing used car values.

There is a chapter dedicated to the history of the Los Angeles Auto Show. Why is this important?

The Los Angeles Auto Show was started by city automobile dealers as a way of selling cars. It immediately captured the public imagination and provided Los Angeles with an opportunity to compete with more established cities by staging bigger and better events. As the automobile industry matured, manufacturers, led by General Motors, began to look at the show differently and started to introduce new designs and features every year. Included in the book is the remarkable story of the 1929 Auto Show where 320 cars were destroyed by a fire that caused millions of dollars in damage. Dealers arranged for the show to continue just 24 hours later at a new venue. It was a powerful symbol of how resilient the local car business had become.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.

Darryl Holter grew up playing the guitar and singing country and rock and roll songs in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His current brand of Americana music draws from country, blues and folk traditions and often tells stories about people, places and events.