Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City, 1900–1930 is the First Major History of Car Dealers at Work

Have you ever wondered how and why Los Angeles became so obsessed with cars? While historians and sociologists have provided numerous explanations, little or no credit has been given to the dealers, who ventured into unknown territory to sell a product regarded by nearly all banks and most businesses as a fad at best.

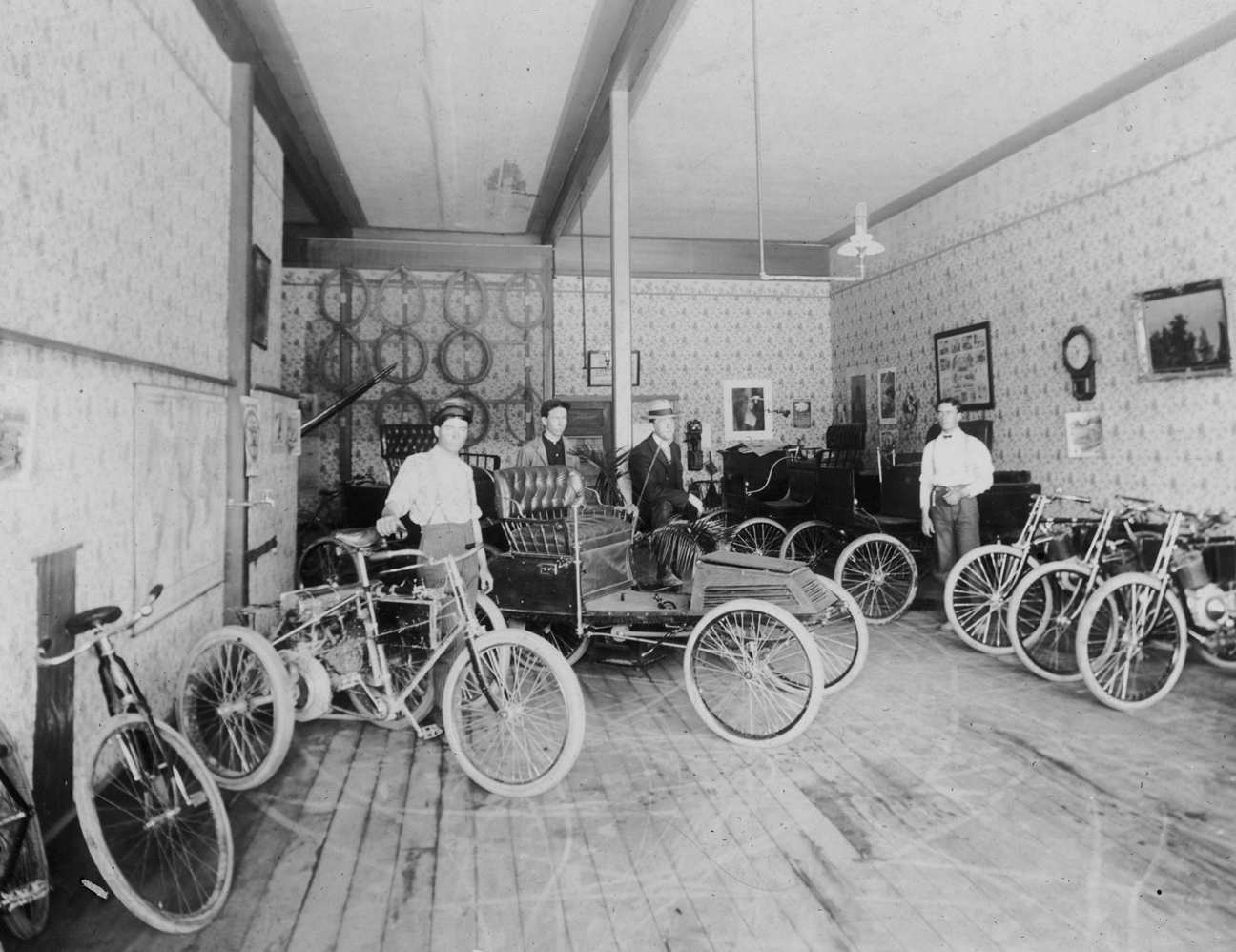

Released on May 9, 2023, Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City, 1900–1930 (Angel City Press) reveals how the city’s passion for automobiles was ignited by an unlikely mix of entrepreneurs and risk-takers. The early days of the city’s auto business owed its inception to the bicycle shop owners who began repairing and selling cars, carriage retailers, and automobile aficionados who learned how to broaden the market for automobiles and convince the public that the car was no longer a luxury, but a necessity.

In this first major history of dealers at work—and one of the first books to chronicle the early history of cars in Los Angeles—authors Darryl Holter and Stephen Gee share the untold story of pioneering auto dealers who seized the chance to join a start-up industry that reinvented an American city. Some became wealthy and powerful, others failed. But the lure of the automobile never wavered. At the dawn of the twentieth century, as Los Angeles transformed from a rugged outpost to a booming metropolis, so too did the fledgling automobile simultaneously come of age.

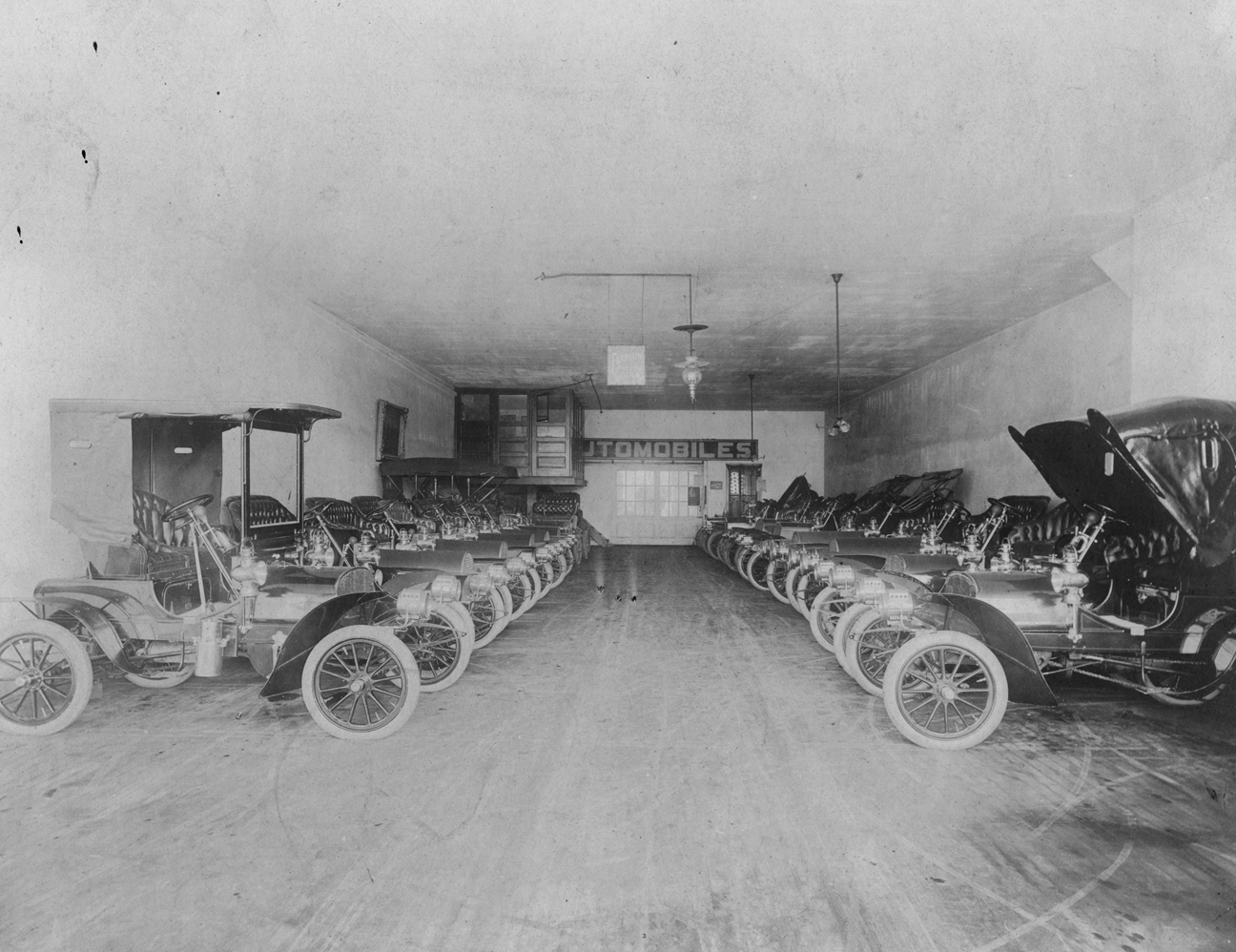

Los Angeles dealers helped change the way cars were sold. They championed selling cars on credit while accepting “used cars” that buyers “traded in” so they could buy a new one. They introduced the West Coast to the concept of dealerships with service bays for on-site car repairs; persuaded manufacturers to design cars to their specifications; and created custom vehicles and innovations that were copied around the country.

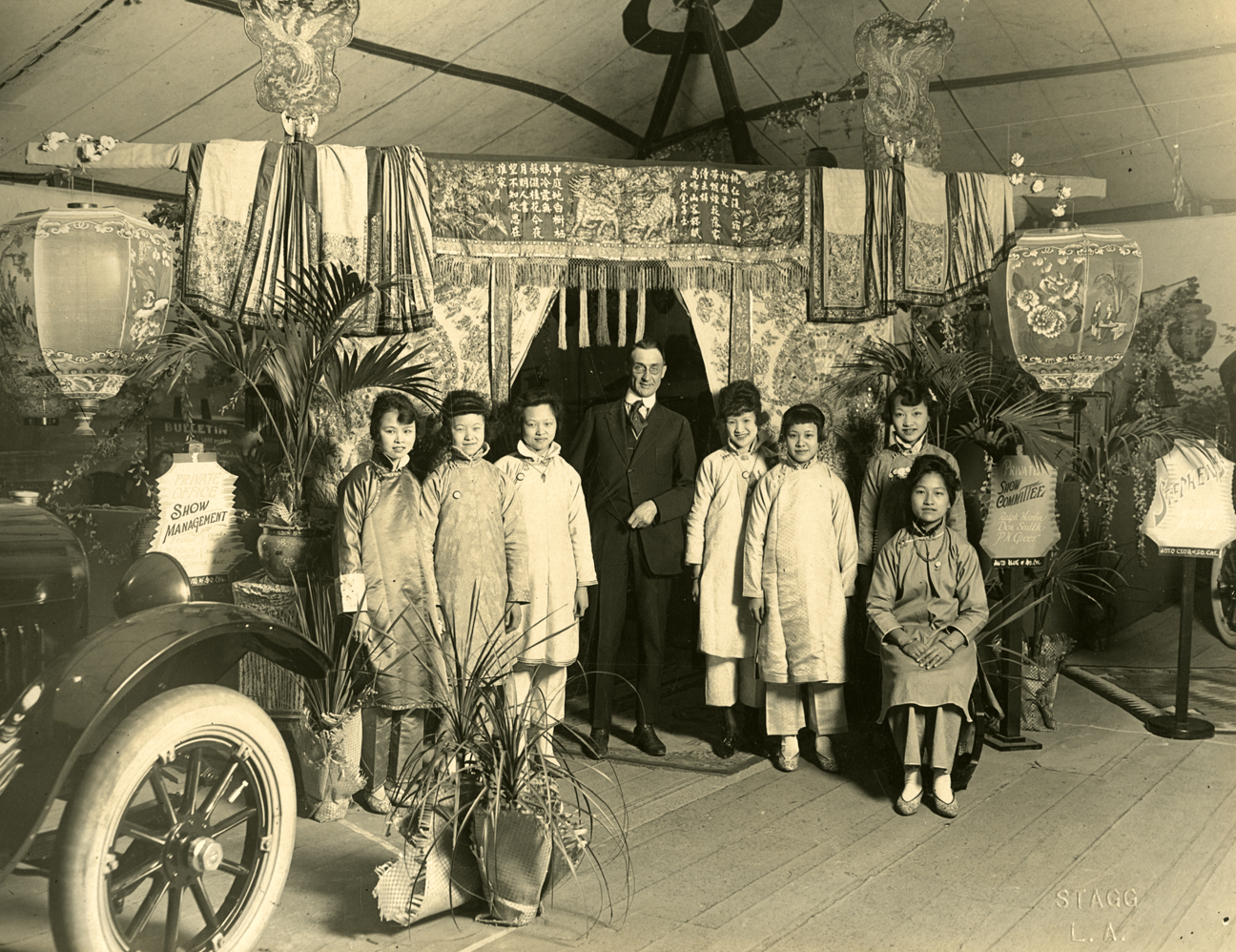

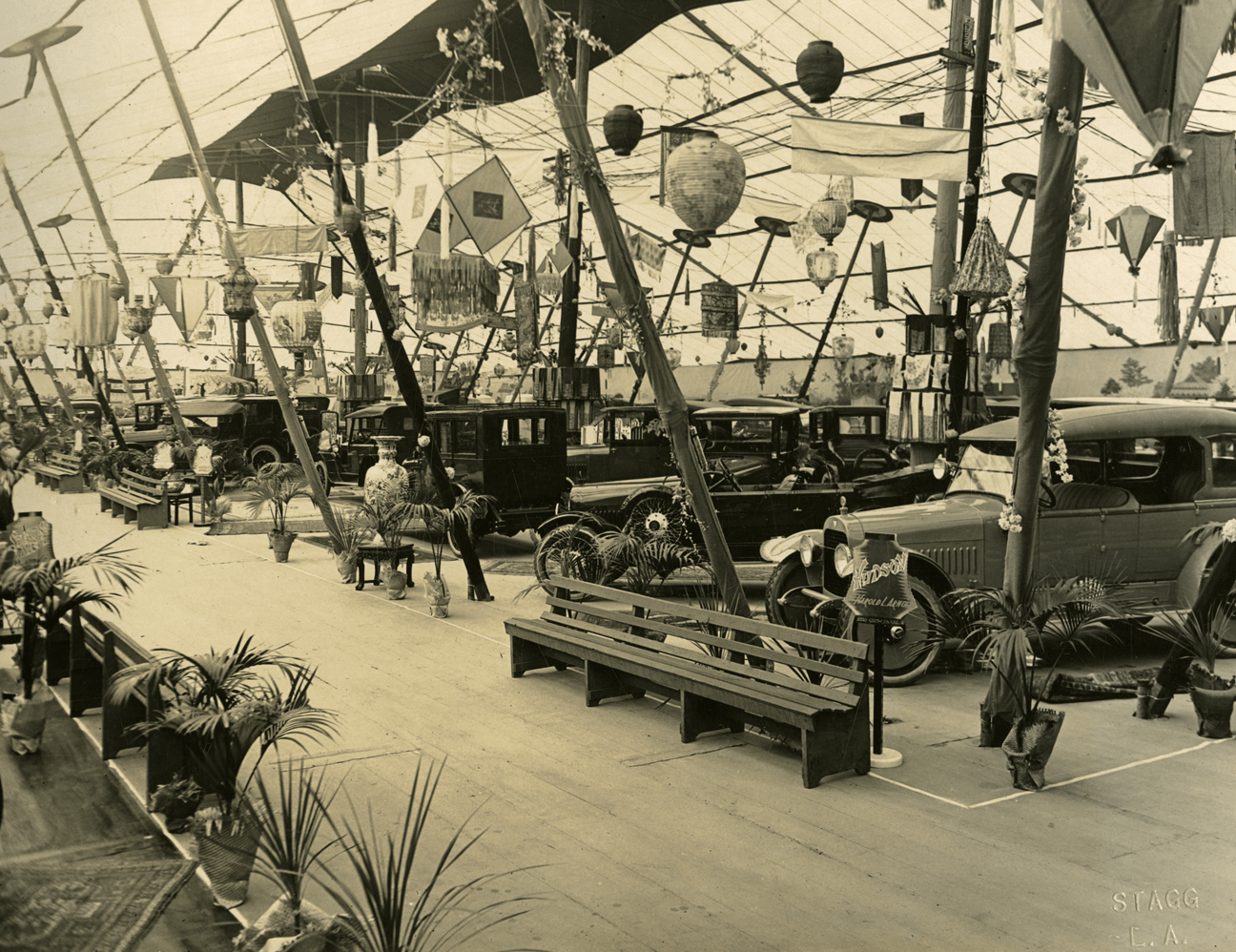

With more than 150 spectacular vintage images—many never before published — Driving Force brings to life the people who made the automobile an icon of the modern American city. In its pages, readers will discover how the story of the automobile is interwoven with Southern California’s unique topography and sun-drenched climate; a new era of women’s rights and a growing female influence on automobile design; the creation of the Los Angeles Auto Show and the remarkable 1929 fire that threatened to destroy it; and how car dealers launched beloved L.A. radio and television stations, including KNX, KFI, and KCBS-KCAL.

Darryl Holter

Stephen Gee

Jay Leno

Darryl Holter

Darryl Holter is a historian, automobile dealer, and musician. His books include The Battle for Coal: Mineworkers and the Politics of Nationalization in France, Workers and Unions in Wisconsin: A Labor History, and Woody Guthrie L.A.: 1937 to 1941. As the CEO of Shammas Automobile Group, he oversaw eight dealerships including the iconic Felix Chevrolet and was the founding Chairperson of the Figueroa Corridor Business Improvement District in L.A.’s historic Auto Row. He is an Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Southern California and a member of the American Federation of Musicians, Local 47.

Stephen Gee

Stephen Gee is an award-winning writer and television producer based in Los Angeles. He is the author of Iconic Vision: John Parkinson, Architect of Los Angeles (2013), and co-author, with Arnold Schwartzman, of Los Angeles Central Library: A History of its Art and Architecture (2016), which won the 2016 Glenn Goldman Award for Art, Architecture, and Photography, presented by the Southern California Independent Booksellers Association. He also wrote Los Angeles City Hall: An American Icon (2018) and Paul R. Williams: Master Architects of Southern California 1920-1940 (2021), produced in collaboration with Marc Appleton and Bret Parsons.

Angel City Press

Angel City Press was established in 1992 and is dedicated to the publication of high-quality nonfiction books. The award-winning books from Angel City Press are sold in fine gift and book stores, and on the Web. Drenched in nostalgia yet undeniably cool, each Angel City Press book is luxuriously illustrated and showcases the modern design concepts of California’s top graphic artists. So it is with the entire treasury of Angel City Press books—each is forever readable, forever giftable. Angel City Press books are published with extraordinary attention to detail, in the finest tradition of the bound page.

Q&A with Author Darryl Holter

Why is the book significant?

This is the first book to explain how and why Los Angeles became so obsessed with cars by highlighting the entrepreneurs who convinced people they were a necessity and not a luxury. It was dealers and not manufacturers who introduced cars to the city. The car-centric lifestyle they championed still defines Los Angeles a century later. What makes this story particularly interesting is that unlike other major cities such as New York, Chicago and Philadelphia, Los Angeles and the automobile came of age at the same time. Cars offered unprecedented mobility and allowed the city to expand to places the rail lines didn’t reach.

How did the book come about?

I was sitting in my office at Felix Chevrolet one afternoon and I got a phone call from the California New Car Dealers Association, our trade group in Sacramento, and they said, ‘Darryl we were moving some things around and we found some boxes with this old material in it that we were going to throw away and someone said you better take a look at it.’ I went up to Sacramento and I found the minutes of the meetings of the Motor Car Dealers Association of Los Angeles, 1905-1920. These are the type of primary documents that historians love to find.

How important were Los Angeles car dealers to the automobile industry?

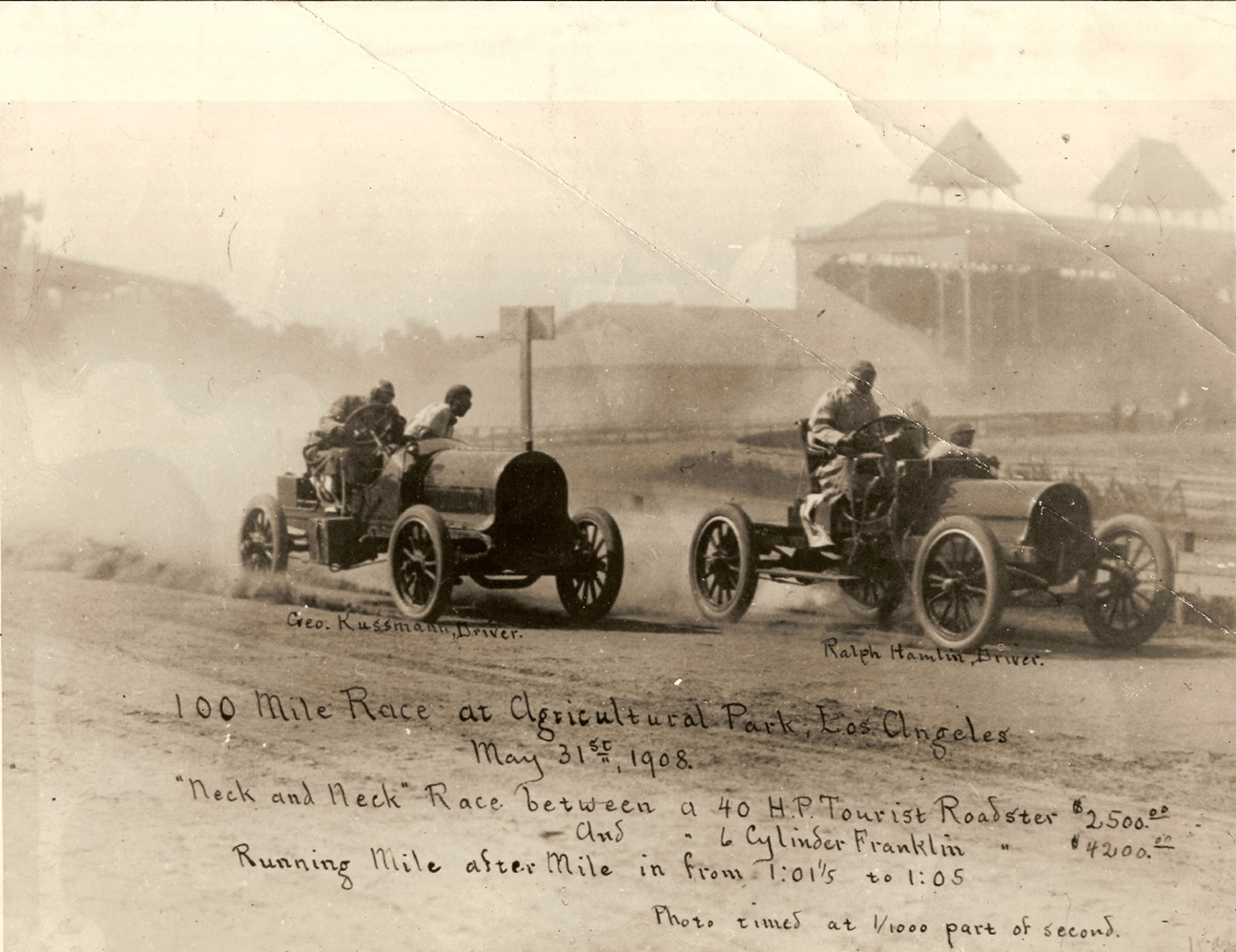

Los Angeles quickly became one of the biggest markets for cars in the United States. There were more cars per capita in Southern California for most of the period covered in the book (1900-1930) than any other part of the country. The pleasant weather and varied terrain encouraged motoring and importantly allowed dealers to sell cars year-round. Powerful city retailers like Earle C. Anthony and Don Lee became statewide distributors for their brands. Ralph Hamlin was the most successful Franklin distributor in the nation and when he demanded the manufacturer modify their cars to his specifications they listened.

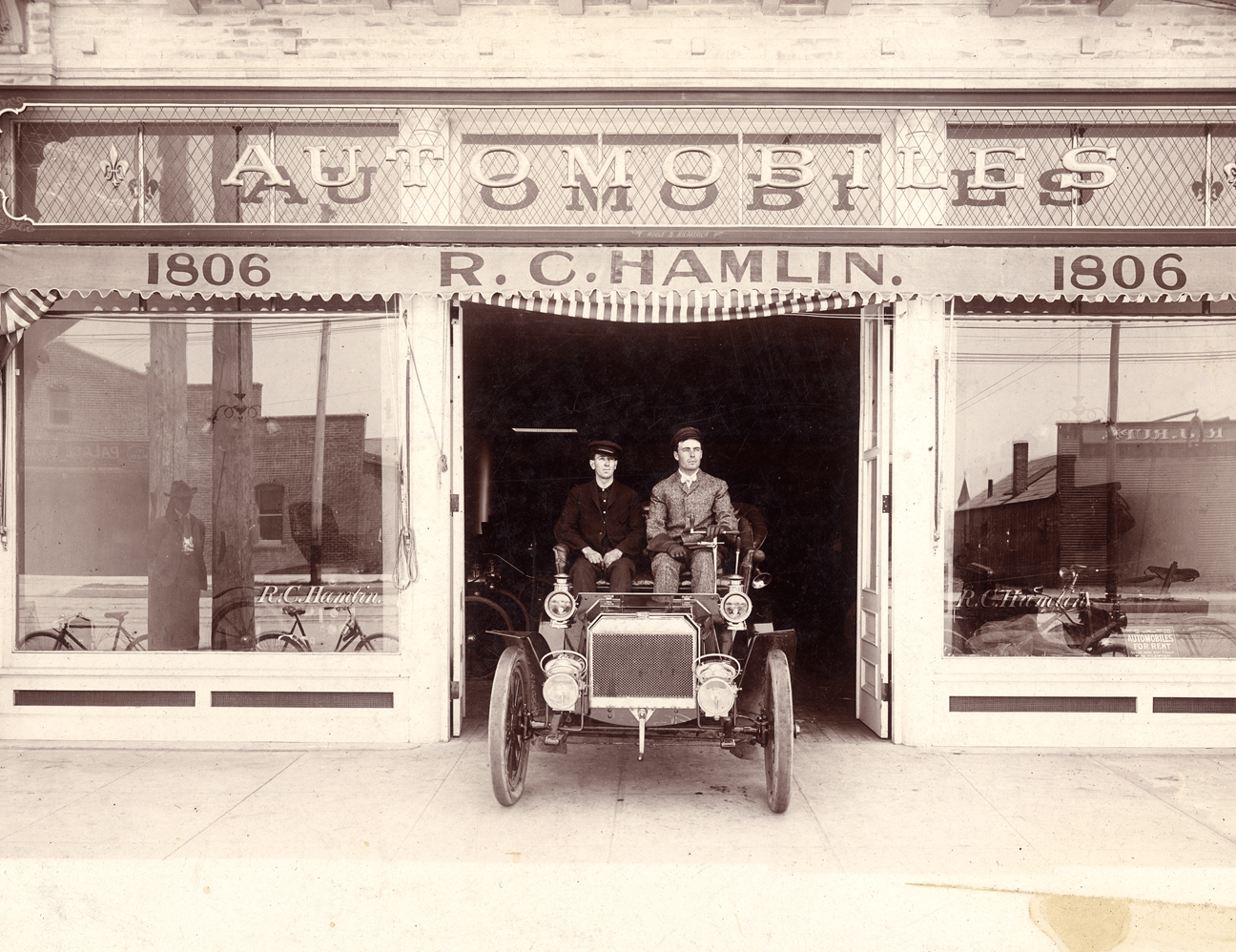

What characteristics did early automobile dealers share?

Many early Los Angeles automobile retailers began selling bicycles before transitioning to selling cars. They had a basic mechanical understanding of how they worked and took a chance on a start-up industry that almost all banks considered a fad at best. A good example is the city’s first car dealer William K. Cowan, who operated the Rambler Bicycle Shop on South Spring Street before making the city’s first car sale, a Waverley Runabout in 1899. Ralph Hamlin also operated a bicycle shop on Main Street before he began selling Franklin automobiles in 1905.

Today Tesla sells cars without using dealerships. Why did dealerships become the main link between manufacturers and customers?

Early automobile manufactures lacked the funds to build a network of retail facilities. They experimented with middlemen, agents and traveling salesmen but ultimately had to rely on local entrepreneurs to sell their product. Carmakers also relied on dealers to provide, through deposits, the working capital they needed to assemble cars. As no factory warranties existed dealers also assumed the responsibility for providing service and repairs. When the market for expensive cars tightened dealers changed the way cars were sold by experimenting with credit sales by accepting down payments and deferred payments.

How important were women to the early car business?

Although women were underrepresented on the sales floor they were incredibly important to the design and marketing of early cars. Many of the innovations that they demanded, such as windshields, electric ignition switches, glove compartments and upholstered seating would become standard features. Women also particularly liked electric vehicles because they weren’t noisy, and they didn’t smell or have exhausts. Los Angeles would lead the nation in terms of the number of women motorists and local dealers competed to earn their business.

How does this book reflect the diversity of Los Angeles?

The automobile pioneers included in the book came from vastly different backgrounds. We shine a light on Mexican American dealer Winslow B. Felix who used Felix the Cat to promote his Los Angeles Chevrolet agency; Ygnacio R. Del Valle who grew up in one of California’s prominent pioneer families before selling Brush cars, promoted as costing less than it costs to keep a horse; Tommy Pillow Jr., one of the first African-Americans to build and race cars in Los Angeles; James S. Conwell who juggled selling cars with his role as President of the Los Angeles City Council; and Sybil C. Geary who transformed the Automobile Club of Southern California into the largest motor club in the world.

How did Los Angeles car dealers use their influence?

While some early dealers and automobile brands failed, others went on to become rich and powerful. Earle C. Anthony, who represented Packard, would form KFI radio and KFI-TV (now K-CAL). He also championed better roads and bridges across the San Francisco Bay.

Paul G. Hoffman, who sold Studebaker cars, launched KNX radio primarily to promote his car business. He would later be recruited by President Harry Truman to help rebuild Europe after World War II. Don Lee, who represented Cadillac, would operate KFRC radio in San Francisco and KHJ in Los Angeles. He would later launch an experimental TV station that later became KCBS-TV. R. Leslie Kelley, launched the Kelley Kar Company and also the Kelley Blue Book, now the industry standard for accessing used car values.

There is a chapter dedicated to the history of the Los Angeles Auto Show. Why is this important?

The Los Angeles Auto Show was started by city automobile dealers as a way of selling cars. It immediately captured the public imagination and provided Los Angeles with an opportunity to compete with more established cities by staging bigger and better events. As the automobile industry matured, manufacturers, led by General Motors, began to look at the show differently and started to introduce new designs and features every year. Included in the book is the remarkable story of the 1929 Auto Show where 320 cars were destroyed by a fire that caused millions of dollars in damage. Dealers arranged for the show to continue just 24 hours later at a new venue. It was a powerful symbol of how resilient the local car business had become.